In this blogpost, Senior Technical Researcher Jared Keller examines 'bottom-up' data institutions, and unpicks the different ways they empower people to play a more active part in stewarding data. We hope this will be useful to others working to understand and encourage new forms of data stewardship, potential funders exploring whether and how to support them, and policymakers working to create an enabling environment.

Deconstructing bottom-up data institutions Individual decision-making Collective decision-making Delegated decision-making Looking ahead

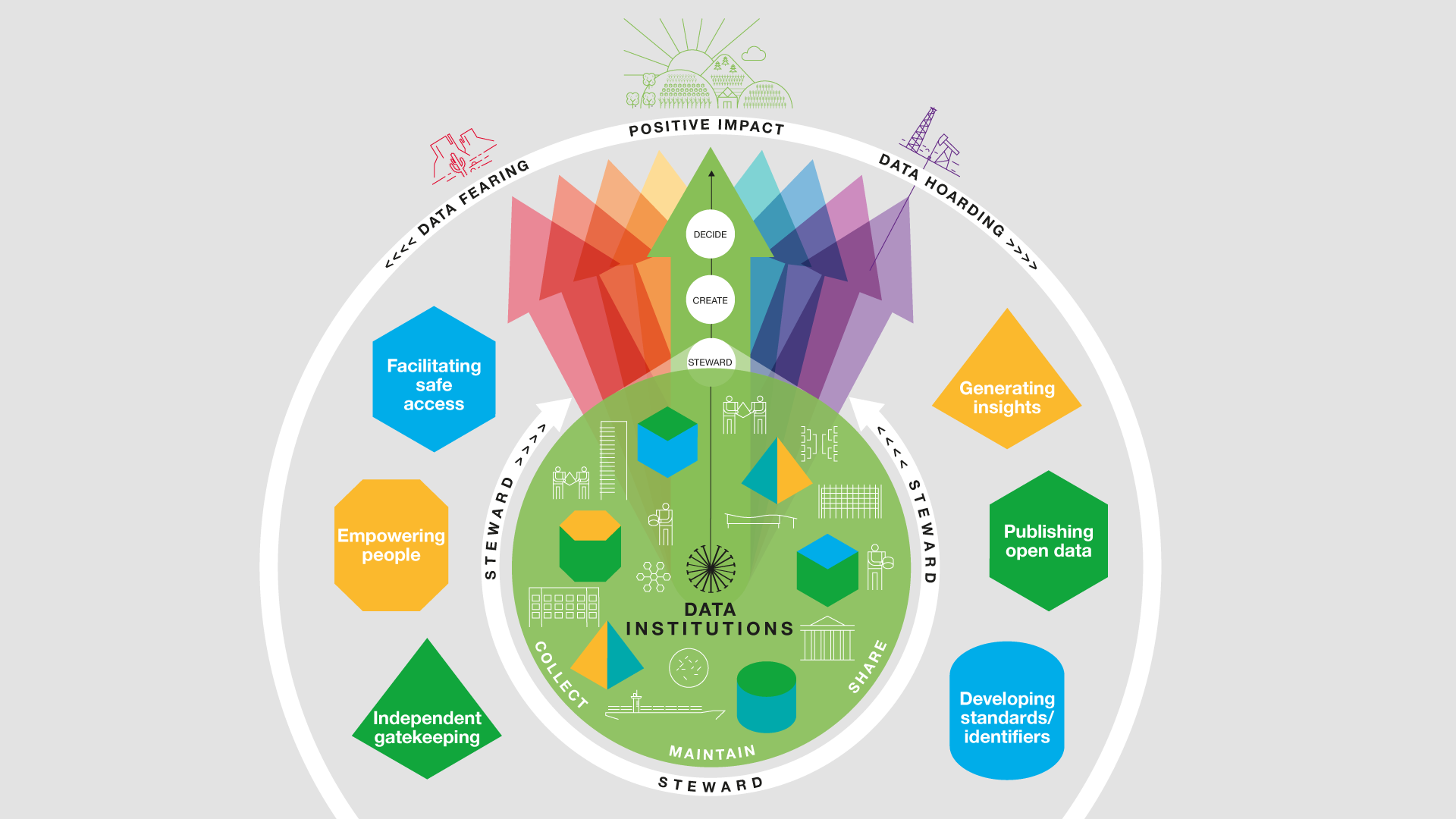

Data institutions are organisations that steward data on behalf of others, often towards public, educational or charitable aims. At the Open Data Institute (ODI), we describe ‘stewarding data’ as making important decisions about who has access to data, for what purposes and to whose benefit, to realise the value and limit the harm that data can bring. In our previous blogpost on this topic, we discussed the relationship between data institutions and stewarding data, and outlined six vital stewarding roles that data institutions play within data ecosystems.

Of those six roles, one that has recently seen a lot of interest from researchers, policymakers and funders is the role of empowering people to play a more active part in stewarding data about themselves or that they have a vested interest in. A lot of the current interest has come from the hope that supporting people in this way will help rebalance the current power imbalance between individuals and corporations, empowering people to use and share data as they see fit – whether that’s donating it to research projects and philanthropic endeavours, or selling it to generate income.

Despite all the interest, it can be difficult to understand what is happening in this space or compare the new ideas, approaches and institutional forms that are emerging from within it.

This is in part because there is so much useful and relevant work happening in this area at the moment. Alongside the ODI’s own work on data institutions, a field has emerged around the concepts of bottom-up data stewardship, including the work of the Data Trusts Initiative, the Mozilla Foundation’s new Data Futures Lab, MyData Operators, the European Commission’s Data Governance Act and the Aapti Institute’s ‘bottom-up data governance systems’.

Another factor is an occasional confusion over terms, with people using the same term to describe different approaches, or using different terms to describe the same approach. Data institutions, like all organisations, are complex and multifaceted, with different legal, technical, commercial, and governance layers. This makes it difficult to assign them overarching labels like ‘data trust’ or ‘data cooperative’ and especially difficult to compare and contrast those overarching labels.

There is really important work to be done to reimagine how data is stewarded, especially to strengthen the role that individuals can play. This blogpost attempts to provide a clearer map of this terrain.

Deconstructing bottom-up data institutions

Most organisations have data governance processes (ways of making decisions about the data they collect and hold). However, the data institutions examined in this post all have processes that enable people – usually those that have generated the data or that the data is about – to actively take part in those data governance processes.

Importantly, our usage of the term ‘bottom-up data institutions’ is in relation to these efforts to include people in decision-making. It is not an indication of how the institutions came into being. Although many of these data institutions are the result of community initiatives, a data institution set up by a government, company or large philanthropic that enabled people to take an active part in decision-making would also be considered a bottom-up data institution.

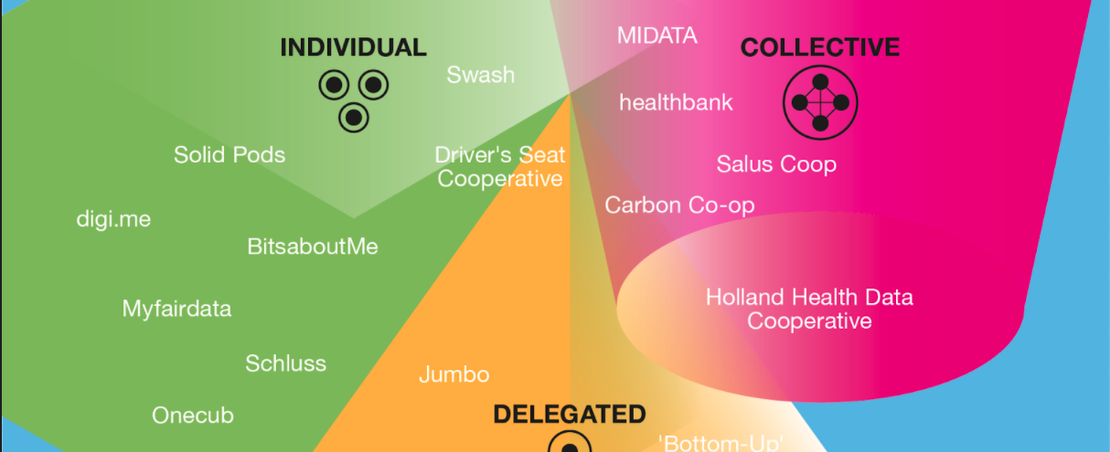

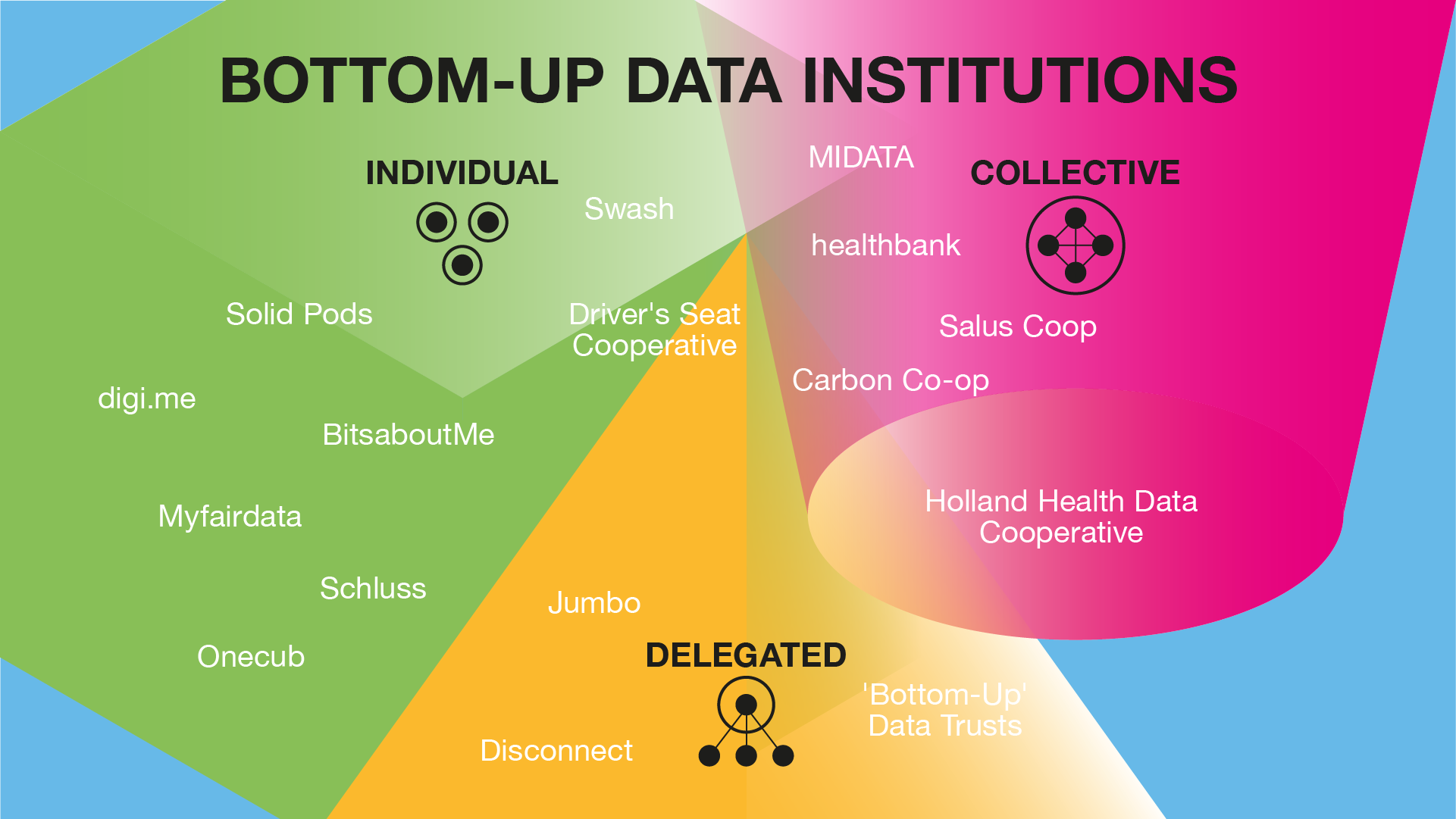

We’ve distinguished three different approaches:

- Data institutions that enable individual decision-making (people making decisions individually)

- Data institutions that enable collective decision-making (people making decisions as part of a larger group)

- Data institutions that enable delegated decision-making (people delegating decision-making authority to another party)

These are not mutually exclusive – a single data institution may, for different types of decisions, employ different types of decision-making.

We can further distinguish between these three types based on whether the data institutions enable people to take part in governing access to data (for example, making decisions about whether to provide access to data to a particular project or group of researchers) or governing the data institution itself (for example, making decisions around the goals and principles of the organisation, plans for future investment, and distribution of profits). The two are intertwined and overlaps undoubtedly exist, but this distinction between organisational governance and governance of access to data is important to understanding the different types of bottom-up data institutions.

We have developed the illustration below to help explain the differences between these approaches and document some of the real-world data institutions that use these different approaches to enable people to play a more active part in stewarding data about themselves and their communities.

Individual decision-making

Some data institutions enable people to make decisions about data on an individual basis. Advocates of this approach believe that giving people individual control over data about them will help rebalance power dynamics that have shifted increasingly in favour of corporations.

For example, BitsaboutMe, aims to help you ‘reclaim control of your digital life’ by ensuring that ‘the decision about sharing data is entirely up to you.’ Similarly, Schluss aims to help you ‘take back control of your data’ and guarantees that ‘you – and you alone – decide who knows what about you.’ Other data institutions employing similar individualistic approaches include:

- SOLID Pods – ‘All your data, under your control’

- Onecub – ‘Our mission is to empower individuals with their data’

- Digi.me – ‘Data can only be viewed and privately shared when you [...] give explicit permission’

- MyFairData – ‘It is up to the individuals, and to them alone, to consolidate or not the personal data that concerns them, to use them as they see fit.’

It is possible to distinguish these data institutions further based on their goals or intended impact. Some of them aim to enable people to share data with others for philanthropic or altruistic reasons; others aim to help people generate monetary value from data about them; and some, like BitsaboutMe, do both.

It is important to note that the decisions that this type of data institution enable people to make are primarily about governing access to data, rather than governing the data institution itself. Users of these services are able to make individual decisions about who has access to data about them, for what purposes and in exchange for what; but generally aren’t included in decision-making about how the organisation providing the service is run.

Collective decision-making

A second group of data institutions enable people to make decisions about data in a collective, participatory or democratic manner. Supporters of this approach tend to believe that individualistic approaches put too much pressure on individuals to make frequent decisions about data. Many also argue that since most data is about multiple people, and the use of data impacts us all, it makes sense to enable people to make decisions about that data together.

The way that these data institutions enable collective decision-making varies; with the main difference revolving once again around whether people are included in decisions about the governance of access to data or the governance of the organisation (or both).

For example, MIDATA enables members to join the MIDATA cooperative and ‘govern the cooperative at the general assembly’ but members are ultimately able to grant ‘selective access to their personal data’ on an individual basis. Similarly, people who sign up to healthbank are able to become a member of the healthbank cooperative, but with regards to access to data, healthbank guarantees that participants are able to ‘share what you want with who you want.’

These data institutions, then, are a hybrid of different decision-making structures, with decisions about the organisation as a whole made collectively and decisions about access to data made individually.

Some of the DECODE pilots appear to fit this mould, as does Salus Coop. In its report ‘Towards citizen governance and management of health data’, however, Salus actually seems to go further towards collective decision-making than MIDATA or healthbank. It advocates for a form of collective advisory/review around data access, in which interested cooperative members would be able to join internal review bodies to review applications for data access. They would then provide guidance and assistance to help other members make informed decisions about those requests for access. In this approach, individuals still have the final decision-making authority, but the guidance that can influence those decisions is produced through a more collective process.

This dynamic extends to data institutions that empower people to take an active role in stewarding non-personal data too. For example, OpenStreetMap is an openly-licensed map of the world, created and maintained by a million volunteers. Although it is described as “not a closely governed or managed project”, some countries reach a volume of contributions to warrant a ‘Chapter’ (a formal group to coordinate and plan activity) and the project and community is underpinned by the OpenStreetMap Foundation.

While there are a handful of data institutions pursuing a hybrid approach to collective decision-making – and interest appears to be growing – it is difficult to locate real-world examples of data institutions that enable people to make decisions about both organisational governance and access to data in a collective, participatory or democratic manner. Part of the difficulty of identifying these institutions comes from the fact that, while many data institutions talk about empowerment, collective action and decision-making, it is often difficult to ascertain if this is decision-making around the governance of the organisation, about access to data, or something else.

Two organisations that have explored a collective approach to both organisational governance and governance of data access are Open Data Manchester and Carbon Co-op. The two organisations are working together to build a data institution to help people play a more active part in how energy data – which can be quite personal – is collected, used and shared. Open Data Manchester writes that they initially intended to create an organisation with a ‘flat structure’ where responsibility for decision-making around consent and data access would be shared between all members. However, they have since moved away from this approach, noting that ‘people value the same data differently’ and therefore ‘the assumption that everyone is equally happy with the same data being shared is a dangerous one.’ The prototype decision-making structures that they have since proposed move away from the collective decision-making approach, instead leaning toward various forms of individual and delegated decision-making for access to data. The next phase of their work will explore the governance of the data institution as a whole, so it will be interesting to see how Carbon Co-op and Open Data Manchester balance organisational governance with governance of data access. In looking ahead to the next stage of their work, Open Data Manchester notes that although their ‘consent mechanism hasn’t been defined yet, it is intrinsically related to how the data cooperative will be governed.’

In part, Carbon Co-op's movement away from collective decision-making around data access seems to be in response to a challenge that other data institutions interested in collective decision-making around data access will need to confront: if the goal of many of these data institutions is to give individuals more control over how data about them is used, does it make sense to make decisions about data collectively if majority decisions overrule individual decisions? Would that mean members who are on the losing side of a decision would then be required to share data in ways they are not comfortable with?

We want to find more data institutions that enable collective decision-making, in particular collective decision-making around data access, and welcome feedback or input from people working in this space.

Listen to our latest data institutions podcast

Jared Keller explores why it’s important for organisations to empower people to play a more active role in deciding what happens to data about them

The Open Data Institute · Rebalancing power dynamics: how data institutions can help empower people and communities

Delegated decision-making

A third group of data institutions are emerging to enable people to delegate decision-making authority over data about them to another party.

For example, services like Jumbo and Disconnect make it possible for users to define parameters for blocking certain types of websites and apps from collecting data about their online activity. Once those parameters are set, whenever users access a website or app, these privacy services will make a decision about whether or not to block collection of data by that website or app, based on that user's preferences. This is more related to delegating decision-making authority around the collection or generation of new data, rather than decisions about access to existing data, but it still involves the delegation of authority to another party.

This type of approach – in which decision-making is delegated based on individually-established parameters – represents another hybrid approach to decision-making.

Carbon Co-op and Open Data Manchester have explored a similar approach to decision-making around data access, which they call ‘Persona/archetype permissions’. In this approach, a member of its cooperative would define ‘a set of behaviours that most align with their outlook'. Members would then delegate decision-making authority to the co-op to make decisions about access and sharing on their behalf ‘on the basis of those agreed behaviours’.

It is early days, but it appears the Holland Health Data Cooperative is also pursuing a similar approach to delegated decision-making. It writes that it is ‘currently developing a module that allows you to easily determine your preferences for sharing your health data for research purposes.’ After that, ‘on your behalf, the cooperative ensures’ collective use of that data in the common interests of the cooperative.

The ‘data union’ Swash also employs delegated decision-making around data in its effort to build a ‘new, fairer, and more balanced digital economy.’ After downloading the Swash browser extension, users are able to individually define: what data is collected about them and their browsing habits, who it is collected by, the level of privacy-preserving transformation applied to that data, and their preferred level of anonymity. After that, Swash ‘works in the background’ to collect, aggregate and sell data on the Streamr Marketplace and distribute earnings back to its members.

It is important to clarify, however, that although Swash is described as a ‘data union’, it does not enable members to make decisions collectively in the way that unions traditionally do. Similarly, Driver’s Seat Cooperative does not appear to enable members to contribute to collective decision-making about governance of the organisation or data access. Instead, by downloading the Driver’s Seat app, gig-economy drivers are able to individually decide to combine their driving data with data from other drivers to gain valuable insights. Driver’s Seat then works to sell this data to municipal agencies on behalf of drivers and distributes the profits back to members. The ‘collective' element of both of these data institutions, then, is less about empowerment through decision-making than it is about 'collective action' and the commercial and analytical power that comes with combining datasets.

The concept of ‘bottom-up data trusts’ seems to conform to the pattern of delegated decision-making. As expressed by Mozilla Fellow Anouk Ruhaak, the idea is that multiple people would ‘hand over their data assets or data rights to a trustee’. By handing over these assets or rights, people would essentially be delegating decision-making authority to these trustees, who would then have a fiduciary duty to make decisions about data access in the best interests of those people. Professor Neil Lawrence and Professor Sylvie Delacroix are exploring the potential of data trusts through the work of the Data Trusts Initiative, as are Mozilla, but more time and support will be needed to determine just how useful they can be in helping people take a more active role in stewarding data about them and their communities.

Finally, some data institutions that pursue delegated decision-making may take a hybrid approach by enabling people to delegate decision-making authority around data access to a representative or board of trustees, while enabling people to take part in the governance of the organisation itself through collective decision-making. Delacroix and Lawrence touch on this when they write that a data trust might be structured in a way that compels the trustees to ‘continuously consult and deliberate’ with data subjects and potential beneficiaries. In this way, the data trust would ‘function in ways similar to a cooperative’.

Looking ahead

As we’ve described above, we think breaking real-world data institutions down into structures and component parts in this way is useful because it helps to isolate the essential things that help data institutions perform their stewardship roles. It also helps cut through the occasional confusion around terms, since it is much easier to compare and contrast specific aspects of a data institution than overarching labels. For example, while 'data cooperatives' are often described as approaches to collective decision-making, the discussion above has shown that, in reality, many real-world data cooperatives are a mix of individual, collective and/or delegated decision-making structures. Similarly, while data trusts are often seen as approaches to delegated decision-making, it is quite possible that many will end up being a mixture of all three approaches.

In the coming months, we will continue to add data institutions to a register that we are building, and welcome help to do so. There is a big world out there and we know we haven't come close to identifying many of the different data institutions in it.

Alongside this work, we also plan to gauge public interest in these types of bottom-up approaches to data stewardship and will work with policymakers to understand how they can support data institutions to perform their vital stewardship roles.

We will also work to examine other roles that data institutions perform. Part of this work will involve continuing to isolate and examine other important structures and component parts of different data institutions.

We would love to work through this process with interested people and organisations, so please get in touch if any of the future work outlined here is of interest. We also welcome feedback on what we could do differently and things we have missed.