At the Open Data Institute (ODI), we want a world where data works for everyone, and our manifesto outlines how this vision can be achieved. One of our manifesto points is about ethics. People and organisations must use data ethically. The choices made about what data is collected and how it is used should not be unjust, discriminatory or deceptive. How could this principle be realised in a national data strategy?

No easy answers

It’s not always easy to do the right thing - and sometimes it’s not easy to know what the right thing even is. In the philosophical study of ethics, a classic thought experiment for moral dilemmas is 'the trolley problem'. Even in these sorts of linear, abstract thought-experiments, it isn’t always possible to get an outcome that everyone agrees on. So we think it’s important that the way in which a decision is reached is as open and inclusive as possible, to build trust in the outcome.

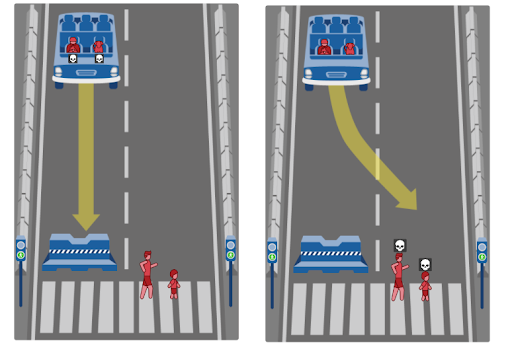

Recently the trolley problem has been adapted by the MIT Moral Machine to explore ethical dilemmas around the programming of self-driving cars, which are a new digital technology made possible by the collection, use, and analysis of data.

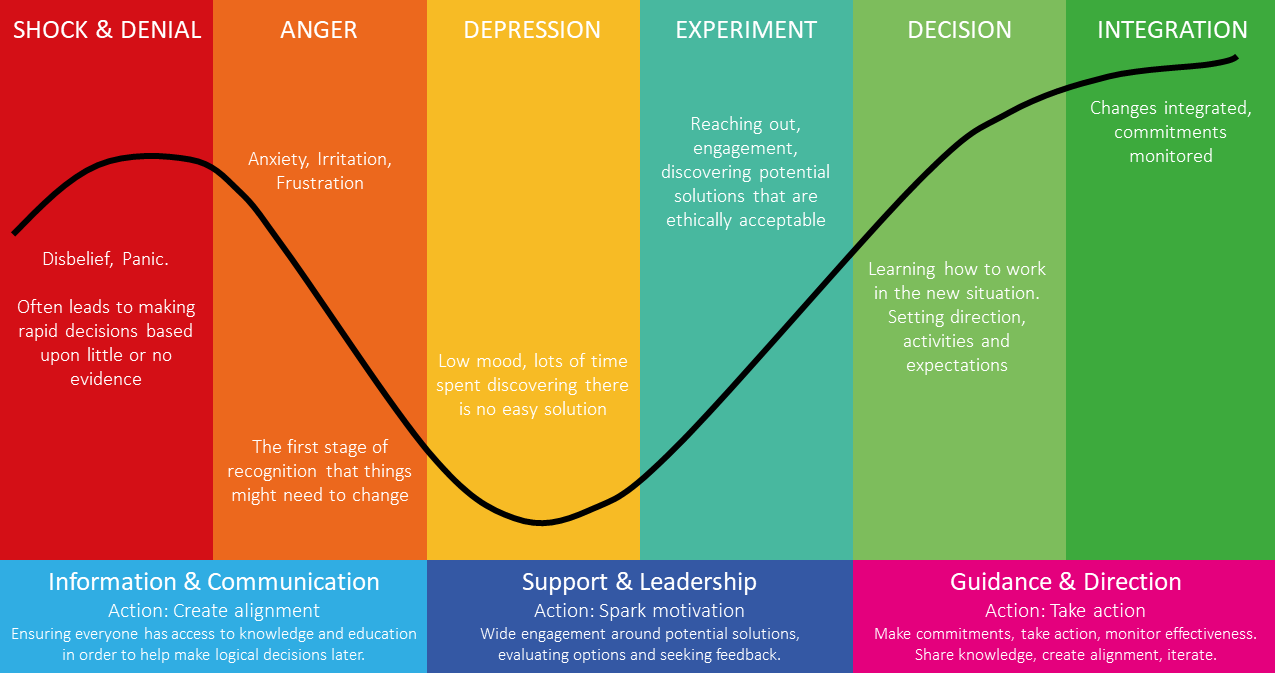

When confronted with a situation where every choice seems to lead to a different kind of harmful outcome, it’s tempting to want to give up. In our Introduction to Data Ethics course, one of the frameworks we explore is the Kubler-Ross change curve applied to data ethics: first reaction, shock and denial.

But doing nothing can still lead to harm: on the MIT Moral Machine, consistently choosing the 'do nothing' option leads to the reinforcement of existing societal biases or structural inequalities, as harms are allowed to happen to those already facing the greatest disadvantages. And so sometimes we must ask ourselves: what are the risks of not trying to do something? It’s important to find a balance between the potential harms of implementing a new digital technology or use of data, and the potential harms or loss of benefits from not trying to use it - particularly when these lost benefits might be felt most by those already facing structural disadvantages in a society.

We'd like to see a national data strategy that is committed to being open and inclusive in its ethical decision making around data, and that recognises lost benefits as well as harms.

Asking the right questions

Embedding ethical practice into data analysis and digital service development is difficult. It can’t be done solely by establishing an ethical checklist because real-world dilemmas are often complex and context-sensitive. It also can’t be done solely by establishing ethical principles because these can be difficult to interpret consistently, and different sets of principles might contradict each other or lose relevance over time as circumstances or technologies evolve. So we believe that a discursive or deliberative approach is a better way to approach ethical decision-making about the use of data.

We created the Data Ethics Canvas as a simple, practical tool for teams and individuals to consider and answer a set of key questions to support their decision-making around data projects. And our Consequence Scanning tool, originally developed by doteveryone, provides technology innovation teams with a set of questions to help them identify and consider the possible impacts of the products they are developing. This more reflective, non-prescriptive approach is also at the heart of our current Data as Culture arts programme on sustainable data ethics.

This is important because a reflective or deliberative approach can help identify new kinds of risks or harms that aren’t captured in prescriptive ethical models. For example, there are ways in which working with data can cause harm beyond harm to individuals - consideration must also be given to harms such as harm to groups, harm to communities, harm to civic institutions, and harm to public goods such as the environment.

So the kinds of commitments we’d like to see in a national data strategy include recognition of the broader scope of ethical data use beyond impacts on individual people, and a commitment to use a range of ethical tools in government’s own use of data in policy making and service delivery.

Our human experience

A powerful and high-profile example of data collection and use is the rise of personalised services driven by advanced data analysis tools such as algorithms. This has made possible a new suite of personalised products and services, particularly in the digital domain - for example, personalised recommendations for film or music streaming, personalised news alerts, and personalised online advertisements. This sort of personalisation, if applied in the public sector, could improve citizens’ experiences of government through tailored access to information and services; it could also support operational efficiency or cost-savings in how services are delivered. But it comes with risks, too: tailored access to information and services might diminish government transparency and accountability. And it might also diminish the sense of collective experiences and shared knowledge that can support a sense of community and social cohesion.

For all the exciting potential of data collection and use, data also has important limitations. Data quality might not always be fit for the purpose it is intended, and this can be an uncomfortable realisation for organisations or data analysts who must then have the courage to think critically about the data assets they steward - a different kind of Kubler-Ross curve experience. And even wide-ranging high-quality data cannot capture the totality of human experience, which means that even the most advanced data analytics might not be the right tool for some kinds of decision-making.

The kinds of commitments we’d like to see in a national data strategy include recognition of the limitations of data, and an appropriately empowered watchdog for digital services and the use of algorithms in the public sector.

Get involved

These are just some of our aspirations for a national data strategy, and some of the ideas we are exploring as we develop our response to the consultation about the UK’s National Data Strategy 2020. We also discussed some of these ideas at the ODI Summit this month (if you missed it, you can catch up on some of the sessions on our YouTube channel).

The consultation is open to individuals and organisations across the UK, and it’s important that a wide range of voices and perspectives contribute to it – so do share and participate.

At the start of this project, we pulled together this spreadsheet to map the different elements of the UK National Data Strategy, to help us plan our response to it. We’ve also made a version which shows which sections of the National Data Strategy we think are most relevant to our ODI manifesto ideas about ethics, to examine those sections in more depth and evaluate them. Feel free to download the spreadsheet and to adapt it for your own use.

If you think anything is missing from the spreadsheet, or you’d like to discuss the ideas in this post, tweet us @ODIHQ or email us.

For more about how we’re engaging with the UK National Data Strategy consultation, please visit the project page.