The ODI is working with the team behind the symptom-tracking app TrackTogether to ensure tracking data is anonymised, open and interoperable

In early May we launched our Covid-19 project funded by Luminate. We did this as we knew that many organisations, people and government are collecting data but might need guidance and steps on how to make it open.

Making data as open as possible enables more people to make the decisions needed to tackle Covid-19 and its wide ranging impacts.

Making the data open means publishing it on the web, in spreadsheets, without restrictions on its use. If this can be done it enables the data that has been collected to be used quickly and without restrictions by the people who need it most and to the benefit of everyone; whether they are in the health service, local authorities, charities, businesses, research organisations, scientists or acting individually.

The aim of this project is to provide guidance and support to make the data, models and software being used to address the coronavirus pandemic as open as possible, while building and maintaining trust and working towards a future where data works for everyone.

The project calls for anyone who might have data to get in touch.

TrackTogether

Just before we launched, in late March when Covid-19 began to impact all of our lives and we headed into lockdown, the ODI received an email from the team that designs the symptom-tracking app TrackTogether. It was a period of time when people were putting their data skills into action to help address the ongoing challenges presented by Covid-19.

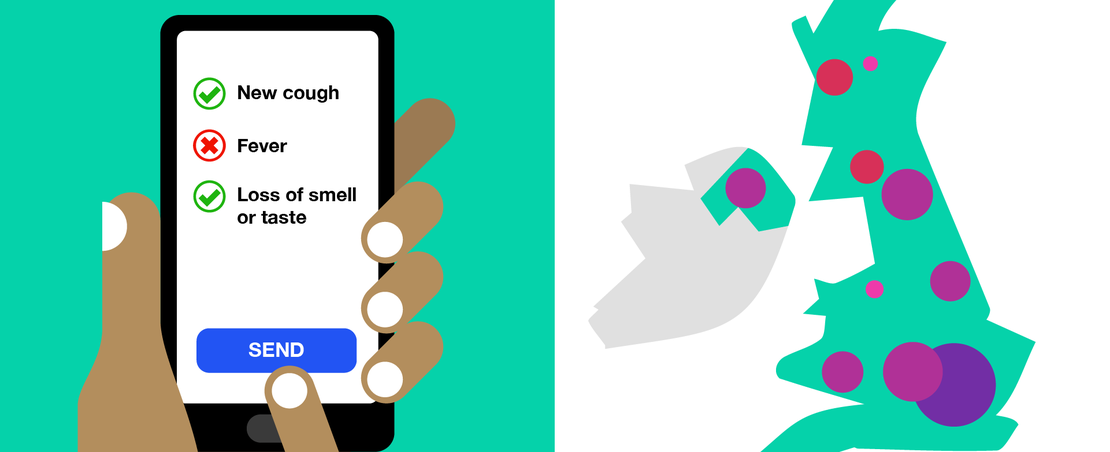

The app, designed around an online kitchen table, was initially used by the friends and friends of friends of Guy Nakamura, Rasheed Wihaib and their team. The app gave users the opportunity to log their symptoms, enabling them to monitor if they were changing or were lasting over a period of time in a way which may indicate they could have coronavirus. The app asked people if they wanted to share details of the first part of their postcode to help identify if there was a spread of symptoms in geographic areas.It was otherwise completely anonymous.

The app gained recognition quickly due to the wide range of friends and family who found it useful and shared it with others who they thought might be interested in not just monitoring their own symptoms but in contributing to the data identifying how symptoms might develop in specific geographical areas around the country.

The app was shared so widely that it fell on the desk of leading researchers and epidemiologists working on Covid-19 at several American institutions, including Columbia University, UC Berkeley and Stanford.

The app was interesting to them as the anonymous, aggregated data could help them with their attempts to better understand the disease, the change in symptoms, its spread; and also the potential ways of monitoring and addressing the complexity of the disease.

Buoyed by the enthusiasm for the value of the data being gathered, but aware that this was a new area for them to get involved in, Guy and his team felt the need to seek guidance and advice. A friend doing research for the team pointed Guy to the ODI. He contacted us and had an initial discussion with Renate from the policy team. It was clear that something exciting was happening but what help did TrackTogether need?

Following the conversation the ODI went back to Guy proposing a range of options: we could connect him with others; offer guidance on ethics, data protection, risk, governance and how to publish openly; help them publish the non-personal data openly; or discuss governance models with them.

The TrackTogether team replied with a ’yes’ to everything.

How we helped them publish open data

Olivier Thereaux, our head of R&D, started working with Guy and Rasheed, exploring how they may be able to publish data openly. Part of it was walking the team through the steps we outlined in our guide to publishing open data in a time of crisis: get the data out there, describe it well, and make sure that it is published with an open licence so that others can access, use and share it.

The TrackTogether team, like most app and software teams, were familiar with the GitHub platform, which can be a good location to publish open data: the ODI’s Octopub open data publishing tool is basically a guided process to publishing data on Github. We agreed that publishing the data there would be easy and convenient.

Once the logistics were settled, the hard work began: the TrackTogether app collects personally identifiable information, and it was clear from the early stages of our conversation that we would need to go through a process of anonymisation before any open data could be published. Anonymisation is not only a good way to comply with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) but is a good ethical use of data.

Furthermore anonymisation is not a one-size-fits-all process, but rather an exercise in understanding and controlling risk: perfect anonymisation does not exist and there is always a latent risk that, with enough time and data, someone may be able to re-identify an individual in an anonymised dataset. Following our guidance, the TrackTogether team felt that they could safely publish a set of open data by removing any personal identifiers from the raw data they held, and aggregate the geographical information to the country level.

The resulting open dataset may not be of great use for anyone wishing to perform detailed geographical analysis of Covid-19 symptoms, but it fulfils three important purposes:

- First, it signals to the world ‘this is the kind of data we hold’. The TrackTogether team has been spending a lot of time talking with researchers about data which they may be able to share, and the publication of open data saves them time by providing a sample of this data, albeit anonymised.

- Second, it is one of the best ways for others to adopt a similar approach to modelling and representing the symptom tracking data. As with every facet of this crisis, the lack of interoperability between various independent efforts is a severe hindrance, and we lack the time it usually takes to design and develop standards. Openly documenting data approaches, schemas and vocabularies used, is an effective way of creating a little more interoperability and nudging the ecosystems towards emerging standards.

- And finally, it opens the door to data discovery, ie. data being found, accessed, used, and shared by anyone.

While there is still much work to be done to curate and ease the discovery of data which may be used to tackle this crisis, the fact that another rich data set is out there, well documented and licensed openly, may help enable better or different decisions to be made, and help get us one step closer to understanding the virus and the ways we can deal with it going forward.

Our work with TrackTogether doesn't end here however. Not only will we continue to work together to publish more open data sets but we are beginning a collaboration on identifying the wider symptom tracker community in order to work together to develop better interoperability and look more closely at the needs for potential standards.

If you are involved in symptom-tracking apps, or if you have data which could be used to help address Covid-19, data that may be valuable in helping us to live in lockdown or help with the decisions needed to get societies moving again, please get in touch with us, and please follow and engage with the #OpenDataSavesLives community online.