This is part of a series of case studies on the value of data collaboration that we are producing as part of our partnership with Microsoft.

Background

The Social Data Foundation (SDF) is an early-stage partnership between three key stakeholders in Southampton – University of Southampton, Southampton City Council and the University Hospital Southampton Foundation Trust. Officially born out of a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) signed in 2021, the SDF exists to research and design mechanisms to improve trustworthy data governance for health and social care.

The goal is to use this data governance to transform and deliver health and care benefits to Southampton and regional communities, while offering a blueprint for others to follow. The approach brings together stakeholders to discover safe, effective and efficient integrated care solutions. The ‘social’ element comes from a desire to include the community and data subjects within the design of the foundation in order to improve outcomes for care and public health. The SDF aims to establish best practice through using and developing open methodologies, standards and open source software – practices which can help the initiative to scale or for other organisations to replicate it across the UK and globally.

The publication of a white paper in 2020 detailed the SDF’s vision and a proposed structure for how to achieve that vision. Through exploring different governance models and ‘deployment scenarios’, the team were able to publicly consider the best options for their work, allowing accountability and generating trust through being open about decisions. The team selected a ‘centralised and query-based scenario’ in consideration of the distribution of control, risk, utility and current technical feasibility.

The ambition is to develop a form of ‘plug and play governance’ whereby ethical decisions can be made at pace and scale, without negatively impacting risk. The best demonstration of this approach is Covid-19 vaccine research in the UK. The abnormal swiftness of testing and approval was not achieved by cutting corners (as the popular misconception goes), but through an alignment of the existing burdensome processes so that they run without the usual vacant time between steps.

Who was involved?

The primary partners for the project – University of Southampton, Southampton City Council and the University Hospital Southampton Foundation Trust – worked together with other partners, such as Microsoft, Privitar, and Trustmark.

Publishing the white paper enabled the collaboration to get buy-in from the stakeholders involved, directly leading to a MoU between the parties and subsequent commitment of time and resources. Specific funding could then be employed to develop the technical proof of concept. Several people working at the hospital and university offered resources in kind by working directly on the project – such as the research and enterprise services, IT infrastructure and governance and security leads.

The functioning of this broad pool of stakeholders is aligned through a monthly operational board and a biannual partnership board (made up of senior people from the main three organisations).

Connecting people through data by building trust

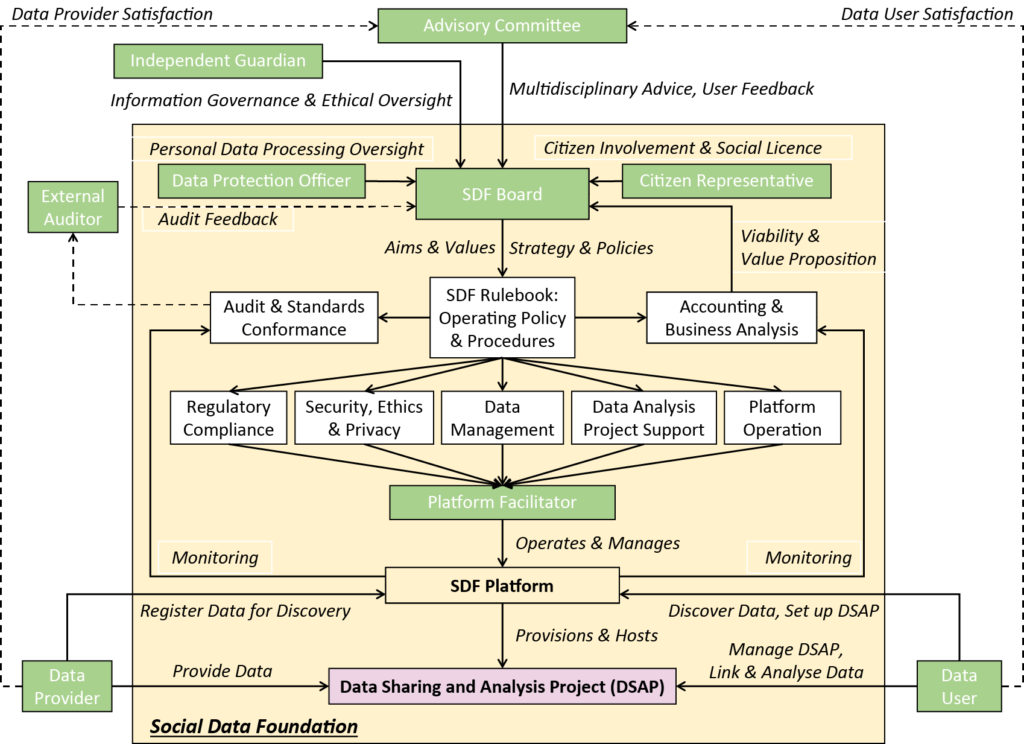

SDF governance. Source: The Social Data Foundation model: Facilitating health and social care transformation through datatrust services (2022)

A driving use case project was selected that targeted the important unmet care need of complex discharge from hospital. Improving the flow of patients from hospitals to communities improves patient outcomes and makes better use of scarce resources while helping the NHS work towards the ambitions of integrated care systems. However, tackling decision-support tools for complex discharge requires collaboration between multiple health and social care agencies and the public to understand patients risks and onward care needs.

The team is developing a set of algorithms to predict which patients in hospital are likely to require onward care using machine learning to analyse likely scenarios. The predictions feed into novel resource planning capabilities developed by the university to ensure that these predictions lead to better patient outcomes and efficient use of scarce resources. This approach is planned to be integrated into decision-support tools for multidisciplinary teams responsible for safe onward assessment and care.

Trust is central to the development of the SDF – with a particular emphasis placed on building trust with patients and the community. To build trust in data and data sharing you need to focus on the communities whose interests are represented in that data, address deficiencies in representation, and engage those communities in data-sharing decisions. This is especially important considering that the secondary use of data continues to increase while patient knowledge or understanding of data usage, risks and benefits remains low.

The SDF team is exploring a range of approaches to meaningful participation with communities, including engagement in data stewardship and the co-design of data-driven technologies. The team believes that community engagement is one protection from the potential risks of using health data – as infamously exposed by 2013’s Care.data fiasco.

Communities must be involved in the co-design of data stewardship arrangements so that interests can be transparently embedded into data governance while social legitimacy and representation are fostered and maintained. Furthermore, through its work on privacy risk assessment – conducted as part of the PRiAM project, funded by UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) as part of the DARE UK (Data and Analytics Research Environments UK) programme – the SDF is working towards a standardised methodology that brings citizens into project-specific data-sharing decisions considering issues of differences in risk perception, self-efficacy and responsibility.

Another aspect of this engagement is involving patients and the public in the co-design of the algorithms. For example, one project called COTADS, funded by the UKRI Trustworthy Autonomous Systems Hub, on diabetes self-management has opened up its code through computational notebooks and interactive interfaces. Patients can ‘play’ with data and models as a way of developing data stories that can expand understanding and foster better engagement for themselves and others. Bringing the community into the project is part of an ongoing vision of ‘a person-centric approach’ to the SDF, and finding new ways for citizens to interact with Trusted Research Environments (TREs).

The biggest factor, and a future indicator of success, is whether the project has managed to abolish the imaginary borders that patients face when accessing health and social care. Patients work across two borders within the NHS – the care provider (social care, community care, hospitals, specialists) and geographic catchment areas – which aren’t relevant boundaries to providing healthcare. For example, a patient may travel out of Southampton to another city or county for a particular type of specialist care. The SDF requires its data to represent this fluidity. Attached to this is a desire for the initiative to grow beyond its current geographic confines, working with partners within neighbouring universities and NHS trusts.

The SDF should also be viewed in the context of the enthusiasm growing around TREs, such as additional NHSX funding to support a Wessex-wide TRE. In 2022, the UK government announced an additional £200m funding to be invested to support better access to NHS data through TREs which, according to Dr. Ben Goldacre (director of the DataLab at the University of Oxford), will ‘drive forward the longstanding ambition to broaden access to NHS data while preserving patient privacy’ and that the building of TREs will ‘support modern, transparent, efficient approaches to data analysis’. The SDF is connected to similar TREs currently operating out of Oxford University and Great Ormond Street Hospital.

Lessons learned and next steps

The pace of technology development within the health sector, combined with the number of overlapping initiatives at a national level requires a high degree of political work on strategy. Strategy in the UK health data context tends to be driven by national bodies such as NHSX and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), in addition to research coordinated by UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) and HDR UK. It is valuable for any new health-related project to assimilate with these strategies and projects.

The SDF is still in its infancy, but its journey so far exemplifies many successes: a reliance on collaboration, building in ethics and equipping the team with the skills to create valuable products – with a focus on governance to match. In a bid to encourage further experimentation across the UK, the SDF shared several key suggestions:

- The interdisciplinary principles as advocated by the British Standards Institute (BSI) have been fundamental in making the project a success, and the commitment to open communities and open source technology enables the project to be replicated to new locations.

- A strong business case needs to be the end result of a period of experimentation. Supporting the sustainability of data access requires a strong understanding of generating sustainable funding/revenue and maintaining trust with the data users and providers.

- The team found that their marriage of informatics and technical science with social and legal approaches is key for tackling issues around data governance and access, and core to building trust with the public and service providers.

- The team emphasises the need for ethics, patient involvement and bringing things together to create trustworthy data sharing and placing equal value on all these components across the collaboration.

- Where practical, build to scale up and out. For example, Microsoft support is all open-sourced. Designing the technical aspects so that other partners can take over and host it elsewhere – or for others to replicate it – is essential to transparency, interoperability and innovation.

The importance of internal championing, such as the determination and dedication of Professor Michael Boniface and Neil Tape, cannot go unmentioned. Linked to this was leadership from an internationally-recognised academic Professor Dame Wendy Hall – enhancing credibility, intellectual contribution and attracting positive attention from senior stakeholders along with national and international recognition.

The SDF will know whether it has delivered on its vision if it deliver benefits to patients, providers and communities. It will need to show the contribution the collaboration has made to make health and social care research easier, enabling new or better services. Other achievements will be if it manages to accelerate access to linked and federated datasets and this fosters cost reductions. Ultimately, it hopes that data providers can make more informed decisions and that there is a decreased risk in data sharing through better understanding, awareness and transparency.

For more information on the SDF see: