Nathaniel Nelson, freelance writer for SmartHome.News, shares five open data projects that are making the world a better place

In 2021, data is everywhere. And most of us have access to little of it.

Tech companies record information about us all day. Government bodies keep detailed records about citizens. Enterprises and industry and even autonomous machines generate tons of data to carry out their operations, but it’s all siloed. Private. Information is proprietary – a commodity, not a resource.

The movement towards open data seeks to change that. Developers, nonprofits and governments are spreading information, allowing anyone to use it, hopefully, to create positive change.

The following are just five open data projects. They cover the full spectrum – infrastructure, energy, education, government and health and safety – but the one thing they have in common: they’re making the world a better place.

1. Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)’s free course material

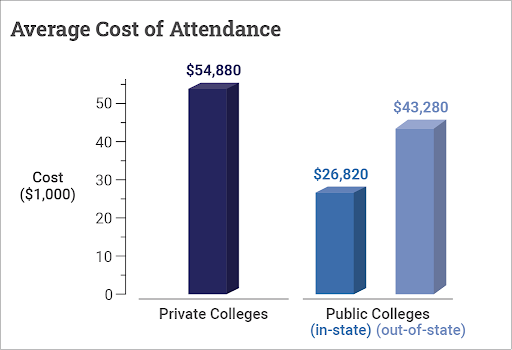

Attending university in many parts of the world is remarkably expensive – often hundreds of thousands of dollars or the equivalent for an undergraduate degree.

Meanwhile, the most prestigious technical university on the planet gives away nearly all their course material for free on the internet.

Long before Covid-19 forced students to sit on all-day Zoom calls, MIT arranged a council to explore the ‘effective application of advanced educational technology [. . .] that will create an exportable model for higher education’. An open and accessible means of spreading knowledge to anyone in the world.

The result was MIT OpenCourseWare: a database of material from real MIT courses, available to anyone with an internet connection. There are over 2,400 courses in the collection, over 100 of which include complete sets of video-recorded lectures. Some include more novel materials like interactive exercises and full, downloadable textbooks.

Theoretically, right now, you could complete an entire degree track from one of the world’s top ten universities. You won’t get a piece of paper at the end, but you’ll have received the best education $200,000 (c. £144,400) could have otherwise bought.

2. Keeping a city moving

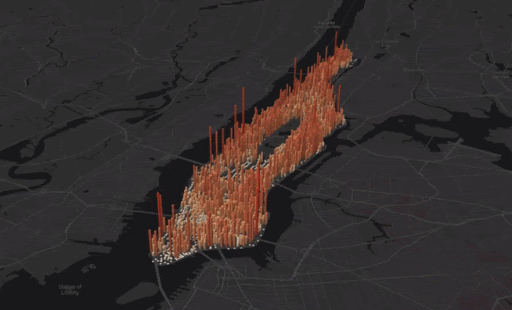

There are about 67,000 residents per square mile in Manhattan. Taken on its own, that’s denser than every major city in the world apart from Mumbai. Count tourists and commuters, and that figure more than doubles. Four million people squeezed into half the square mileage of Disney World.

If 8 million people were to visit Disney World, Florida at once, you wouldn’t want to wait in line for Splash Mountain. But that’s sometimes what it feels like to drive through the busiest areas of New York City.

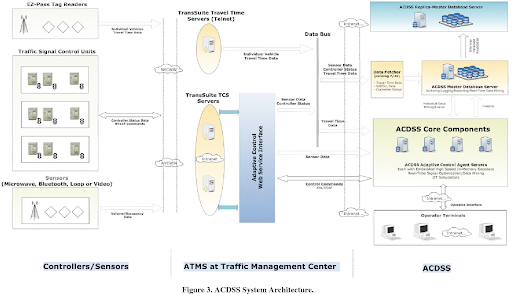

The city government uses all kinds of tricks to try to cut down on traffic, like coordinating traffic lights and congestion pricing. Perhaps its most innovative idea was the award-winning ‘Midtown in Motion’ project – one of the first movers in the trend towards smart cities. The system integrated microwave sensors, traffic cameras and E-ZPass readers across the city, feeding data to a central controller in order to more effectively manage traffic signals and public transit.

The icing on the cake was that all of the data captured was also made available to individual motorists and app developers. That meant city workers didn’t have to do all the work, because drivers and their consumer apps could also take the data into account.

Midtown in Motion led to a near-immediate 10% decrease in midtown traffic, with greater efficiency added as the program expanded. It also set a precedent that has lived on through many other cities’ Internet of Things (IoT) traffic programmes.

3. Engaging local citizens

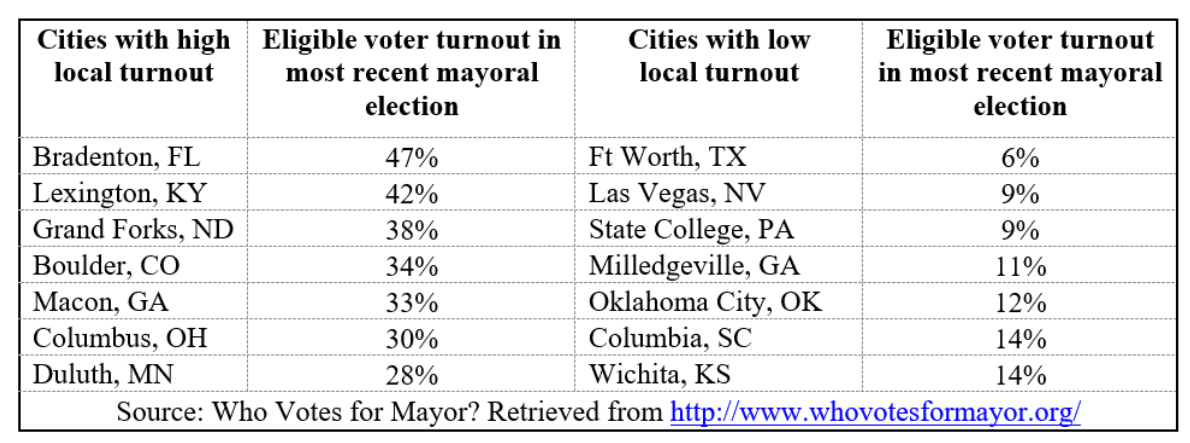

In practice, your life is most directly affected by local government. But in the US, most people don’t follow smaller electoral races or results. For example, local elections average 20-30% turnout, with some cities and towns reaching single digits.

In 2016, a Chicago-based nonprofit called City Bureau launched a program called Documenters, which paid ordinary people to visit city government meetings, then write about or record them. The idea was to increase local civic participation. But Documenters ran into a problem: in a big city there are dozens of major agencies, hundreds of committees and boards. Each of these entities had their own systems, their own websites, making it really difficult to find out when things are happening.

To solve that problem, Documenters teamed up with City Scrapers: programmers who scrape data from all of Chicago’s various civic websites, and collect them in a single database. Scrapers make it easier for any Chicago citizen to find out what’s going on in their area, and become involved. The goal is broader involvement in the political process – higher voter turnout and more accountability for politicians.

4. Giving people control over their home energy

Open data is sometimes associated with the IoT – and for good reason. But there’s another technology that specialises in open data processing: blockchain. The first blockchain was designed to allow permissionless and transparent currency transacting to ordinary people. And ever since the launch of Bitcoin, the prevailing philosophy of blockchain has been to give more people more control and visibility over their data. That means more control and visibility over finances, storage, streaming, or, in the case of Power Ledger, energy usage.

The concept behind Power Ledger is that people would benefit from having more control over the energy they use – volume, cost and type. Using its platform and its native cryptocurrency, homeowners (in eligible areas) can buy and sell excess power on an open market. Because the system is transparent and decentralised, individual homeowners have full view of what a MW of power will cost them at any given time, but also where it came from and by what means it was produced. The system incentivises price competition, energy efficiency and more frequent use of renewables.

5. Collaborations between data aggregators and app developers

A lot of the best projects in open data are collaborations between data aggregators and app developers.

For example, the Chicago Data Portal collects and publishes data from across sectors of the city. That inspired a partnership between two city government agencies, and AllState insurance, to develop models that could predict food inspection violations. As a result of that collaboration, inspectors were deployed more efficiently and they identified dangerous situations more quickly.

Another good example of symbiosis through open data is BlindSquare. BlindSquare is a mobile app that helps blind people get around more quickly and safely by speaking to them – identifying public intersections and points of interest. It’s exactly the kind of thing that the creators behind OpenStreetMap might have hoped their platform would be used for. OpenStreetMap is a completely free and free-to-use world map, developed almost entirely from scratch by volunteers. It’s the kind of thing that can be used to support an app for the blind, or 1,001 other apps that haven’t yet been created but should.

We need more open data

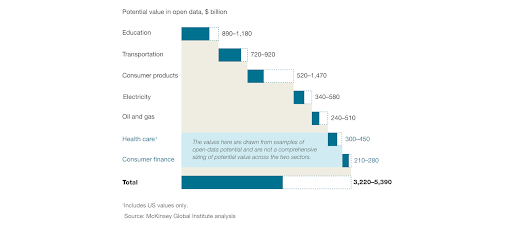

Back in 2013 – when IoT was less advanced and less widespread than it is today, McKinsey estimated the economic impact open data could have in America. They concluded that if even just seven sectors of the country’s economy adopted broad open data practices, it would create $3-5tn in value.