This is the second provocation in a three-part series on critical data infrastructure as part of an Open Data Institute (ODI) project: Power and Diplomacy in Data Ecosystems. These three initial provocations help to demonstrate how we have begun to explore topics related to international data ecosystems, physical infrastructure and dynamics of power. All three provocations will be probed and challenged through a workshop with key researchers and through a joint project with the ODI’s Data as Culture programme. As discussed in our first provocation, the internet is material, tangible and concrete, as are data centres, satellites and undersea cables. This piece focuses on the actors who own (and invest in) this physical infrastructure holding the internet together. The undersea cable sector has experienced a revolution since the arrival of tech companies who, in less than 10 years, have managed to grab large shares of the market by financing colossal projects from beginning to end. The more the network gets increasingly huge and complex, the more it reveals a complex cartography of the major geopolitical (im)balances. This provocation and the related roundtable discussion, aims to unfold the risks and threats posed by the ability of a (very) small number of actors to dictate terms and control the flow of information across the globe as well as the opportunities of this ownership.

What are undersea cables?

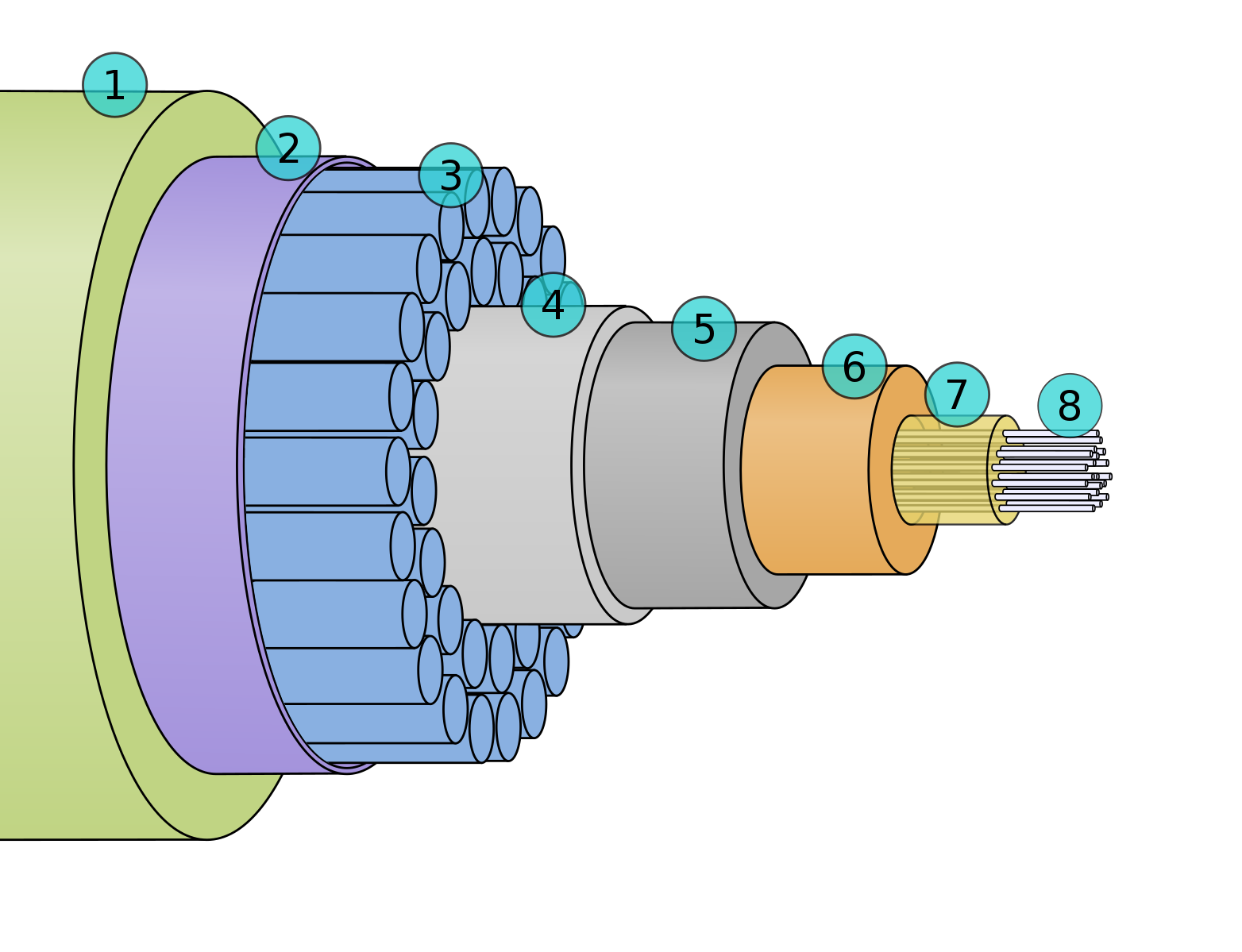

A submarine cable is a cable laid on the seabed (or sometimes buried) to carry telecommunications or electrical power. About 99% of intercontinental communications (internet data and telephone traffic) are transmitted across 450 fibre optic 'lines' spread across the bottom of the ocean. Submarine cables are laid and maintained by cable-laying ships, following very thorough analysis provided by the cable operator to identify the ideal route. These cables are made of fibre optics and form a vast underwater web, covering approximately 1.2 million km of the ocean floor, which is more than three times the distance from the Earth to the moon. To protect both the signal and the physical infrastructure of the cable (from sharks and clumsy ships, as well as maritime trade and erosion), the cable is covered in different materials like silicon gel, plastic, steel wiring, copper, and nylon.

Similar to the benefits of ethernet connections over wifi, submarine cables overcome two limitations of wireless satellite connections.

- Latency: the cable avoids the time loss caused by the distance needed to make a satellite transmission

- Bandwidth: The wire connections are more reliable and powerful than wireless ones

The added value of undersea cables should not only be assessed from a technical perspective. Cables also provide the privacy and security that satellites lack.

History: from public to private infrastructure

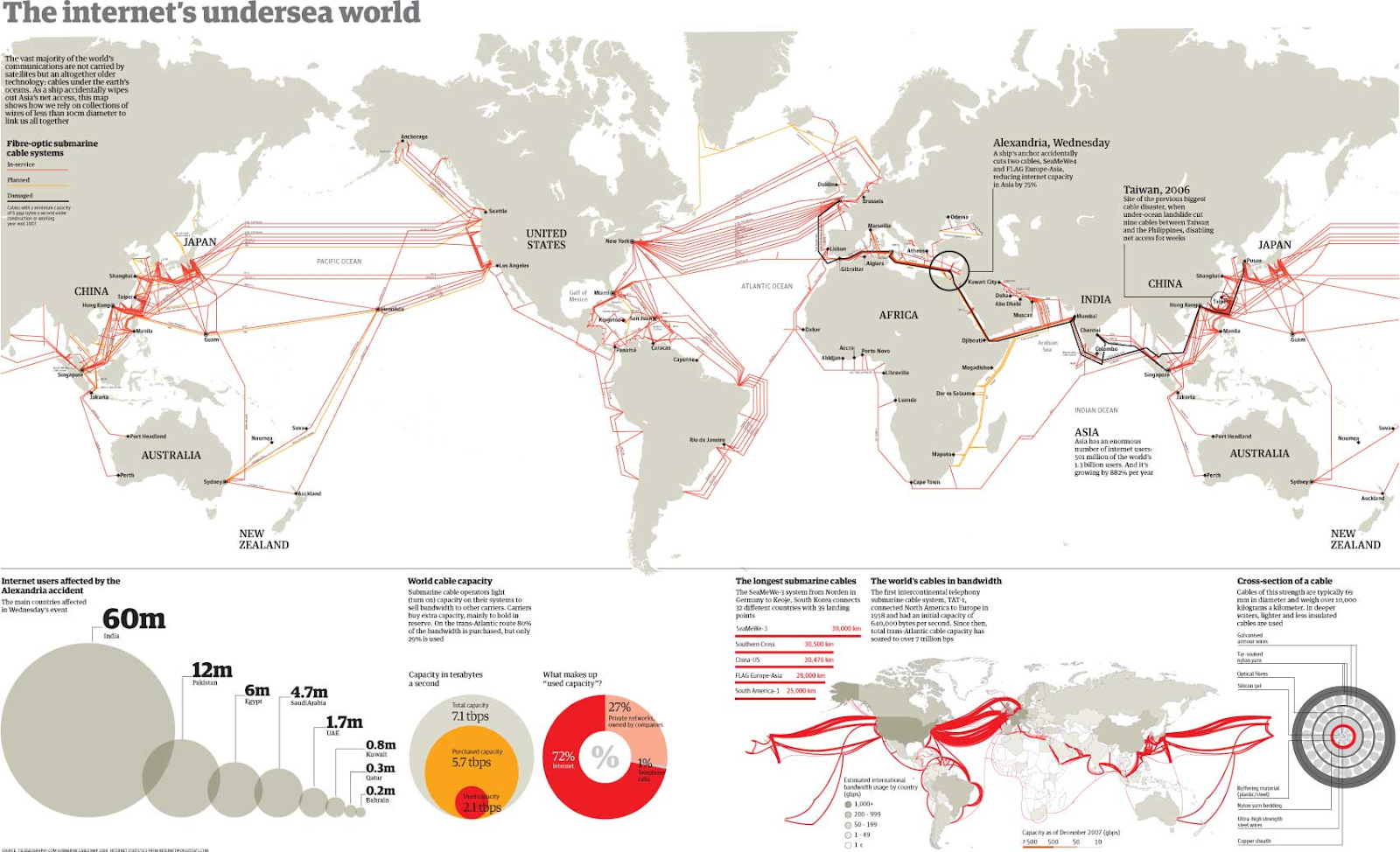

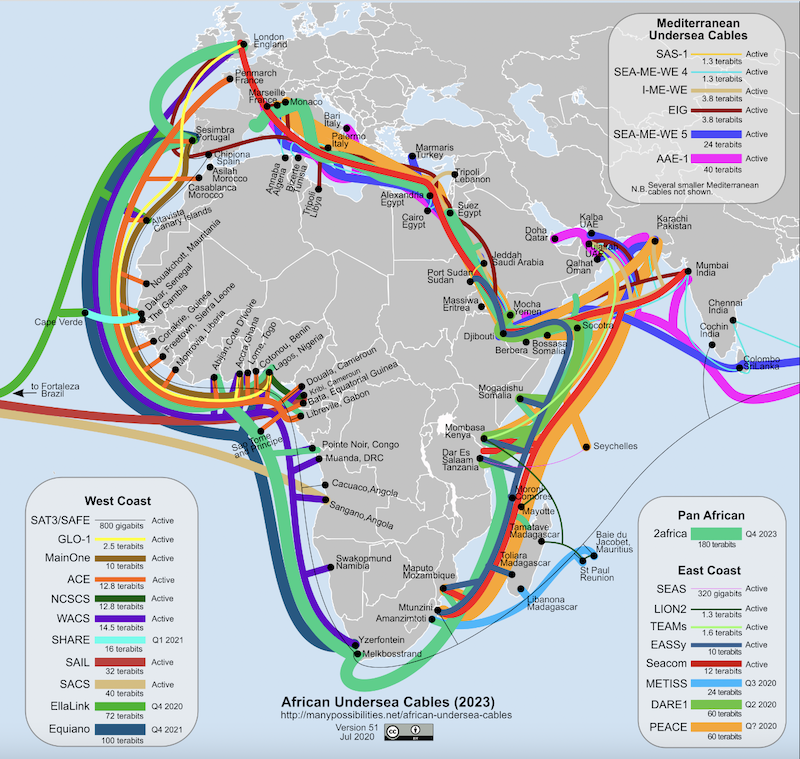

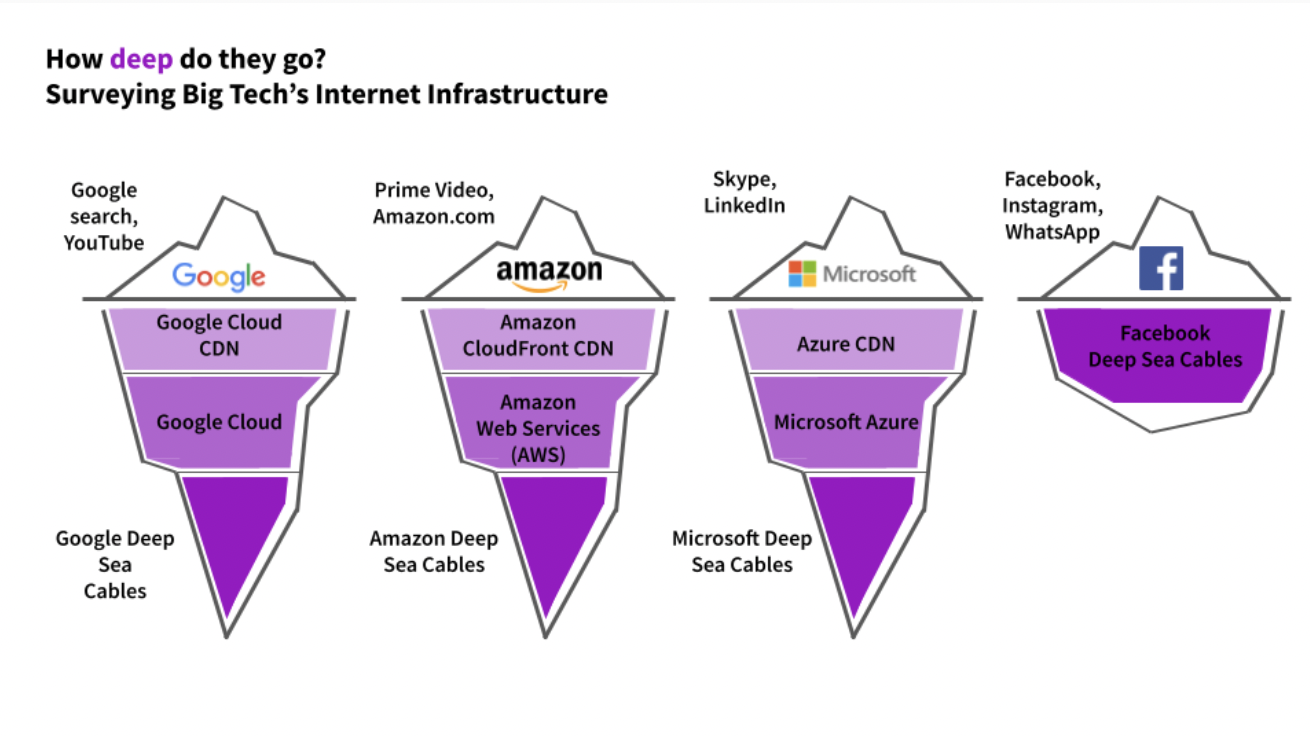

Source: Submarine cables world map in the Guardian. Full-size version (Graphic: Telegeography.com)Historically, subsea cables were owned by telecommunications companies that were state-owned companies but since the 1990s, these became private or semi private entities. Now, these cables are mostly owned by consortiums, including telecommunications carriers and other parties interested in using capacity on the cable. Operators in countries with a coastline, such as Orange (France), British Telecom (the UK) and Telefonica (Spain), were equipped with their own fleet of cable-laying ships to repair and use the submarine cables. In the last 10 years, as the telecoms market has opened up to competition, a few tech giants have become owners of this infrastructure by creating new submarine cables. In recent years, having exerted their outsize and unprecedented influence over cyberspace, they are now conquering the physical infrastructure of the internet, by creating an infrastructural monopoly on a global scale. In 2010, the four major tech companies (Google, Meta, Microsoft and Amazon) owned only one cable in 2010, connecting the US and Japan. By 2024, they will possess more than 30 long-distance cables connecting every continent. Owning both data centres (Amazon, Google and Microsoft have over half of the world’s hyperscale data centres) as well as submarine cables, these companies are increasingly dominating the spatiality of the internet. Through competition for market dominance we have seen the consolidation of the internet's physical infrastructure in the hands of a few. The recent acceleration and increasing investments of tech companies in the submarine connectivity cables market (doubled since 2017–2018 to the present), is a new parameter to consider, according to the President of Alcatel Submarine Networks (ASN). Approximately 70% of ASN’s projects are now funded by Google and Meta, including the largest subsea project ever conceived (52,000 km long), 2Africa, passing from Europe, going around Africa, through the Suez Canal and the Mediterranean and back to Europe. Partnering with telecommunications companies (Orange and Vodafone), Meta has taken 60% of the capacity (see image below).

Facing growing demand for bandwidth, it appears tech companies want to free themselves from certain costs imposed on them by telecommunications operators according to the French expert on submarine cables Camille Morel. By launching their own cables, these private companies are extending their control over the architecture of their data around the globe. Researcher Camille Morel explains in this interview (French language) that the latter ensures they can choose the route of these lines and the countries of destination, to be more resilient in the event of network difficulties.

Image credit: Bot Populi: Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

Implications of the privatisation of internet physical infrastructure

The change in ownership of Twitter by Elon Musk has raised questions around the implications of the corporate hegemony over digital platforms. Likewise, the implications of the increasing privatisation of the physical infrastructure raises questions about what these actors could do with so much (internet) power – cutting off countries from connectivity for political reasons for instance. The hegemony over physical internet infrastructure is still far from being sufficiently documented and explored despite the high stakes and challenges.

Law, regulation and governance

Law

Given the extent of the international and cross-border dimension of the cable network, regulation has not been an easy task. The earliest international law agreement on the topic is the Convention on the Protection of Submarine Cables, signed in Paris in 1884. The treaty applies to all cables outside the territorial waters of states and requires all states to incorporate its protections into their domestic law. Since then, this international collaboration on cables has gradually increased the role of states and their scope for action. Indeed, the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) superseded the 1958 Geneva Conventions and extended states' territories by 200 nautical miles by establishing Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZs). Besides, UNCLOS recognised the freedom of all states to lay cables within their EEZs and extended its protections to cables within the EEZ. Beyond those EEZs though, rights and responsibilities of both states and tech companies regarding submarine cables are ambiguous and blurry. In Article 79, UNCLOS recognises the freedom of all states to lay cables on the continental shelf. Therefore, if this principle extends to private tech companies, what will happen if they get into states’ EEZs? Could companies have the same room for manoeuvre as states? What will happen if they do? Could there be potential arm wrestling between state and private actors? This evolution raises broader questions around the future of international regulation.

Regulation and governance

Given the lack of international regulation, researchers Christian Bueger and Tobias Liebetrau highlight some ideas such as:

- creating a national cable protection zone integrated into the structure of the UN counterterrorism conventions, the development of an international agency integrated in the UN system

- additional laws

- creating an international regulatory body

As it is, the legal framework surrounding undersea cables is made of an insufficient legal mix (international conventions and customary law) and the location of these cables in international high seas makes the regulatory task even more difficult.

Global connectivity

The recent multiplication of tech companies’ investments in submarine cables has been officially promoted as an ambition to connect people and continents worldwide. If connecting hard-to-reach places should be a major challenge and a collective ambition, the underlying question raised by this monopolistic ownership is the question of consolidation of power by mostly US-based companies. Isn’t it somehow ironic that the more the world gets connected, the more the global digital resources become centralised and hyperconcentrated? Will this monopolistic ownership undermine international collaboration around submarine cables? Could the undersea cables become levers of conflict in the future? Could we see a renewal of historical maritime rivalries? Could the infrastructure become a new object of intense rivalry and conflict between states? Siloing data and consolidating power within the hands of a few can lead to unhealthy data ecosystems, where profit and public interest might be dangerously at odds. Transcontinental fibre optic cables, internet exchanges, monopoly service providers and geographically concentrated data centres have all helped build a grossly asymmetric network, in which communications, rather than being broadly distributed, travel through key hubs, which are differentially concentrated in the United States, and channel the most global data exchanges (Weaponized interdependence) There is a global imbalance of connectivity. Until recently, East Africa represented less than 1% of the world’s broadband capacity, while it is one of the most populated regions in the world. In comparison, 49 of the 265 submarine cables in service in the world are connected to the UK territory. Almost all the Europe-America exchanges transit through it.

Risks and attacks

Undersea cables as objects of geopolitical tensions and/or collateral damages of conflicts is increasingly a pressing issue. When we talk about submarine cables, there are two dimensions that could be subjected to geopolitical threats: first, the physical integrity of the cable, and then the data passing through those cables.

Damage

Thousands and thousands of kilometres of deep sea cable constitute the backbone of the functioning of our societies. It would only require slight damage and the consequences would be severe. Therefore, this tells us that the risk needs to be spread and managed worldwide so that aspects of communication are not reliant on single points of failure. While the physical integrity has only been unintentionally affected by conflicts so far, there is always a risk that this could change as the geopolitical scene evolves. For example, a malicious actor could attempt to intentionally damage submarine cables. One example would be the ability of some surface ships to destroy parts of cables, such as weaponised civil vessels like the famous Russian Yantar. Indeed, NATO forces spotted some Russian vessels near critical communications networks, which has raised concerns that these might be targeted if a conflict was to develop. Another example could be manned submersible technologies that are increasingly widespread and not only reserved for naval military forces, which could lead criminal organisations or malicious state actors to damage undersea cables this way. Interception Regarding the surveillance and interception of data, the Snowden case revealed that the American and British secret services have already collected data from undersea cable landing stations, by tapping the cables with different surveillance programs, therefore raising questions of extra territorial competencies. Public acts of piracy have been rare but could have major impacts if they were to increase. Despite encryption techniques, protective physical measures and increasingly powerful monitoring software that can help detect network irregularities, malicious ‘cyberattacks are more likely to occur than physical breaches on land or at sea’.

Ecology

Studies have shown that cables pose minimal impacts on life in these environments. Data from 1877 to 1955 showed a total of 16 cable faults caused by the entanglement of various whales. Such deadly entanglements have entirely ceased with improved techniques for placement of modern coaxial and fibre-optic cables which have less tendency to self-coil when lying on the seabed. Another way of looking at ecology here would be to consider how climate change and its implications could affect the critical infrastructure of the Internet and particularly undersea cables. For instance, rising waters could erode the beaches where the cables make land, increasing the number of underwater storms and earthquakes leading cables to break.

Conclusion

This critical infrastructure is physical, geographical and therefore reveals offline power imbalances and subsequent competition between countries and private actors. This article aims to demonstrate that the control over submarine cables is eminently strategic on both an economic and geopolitical level. We invite anyone interested in this topic to get in touch with the Power and Diplomacy in Data Ecosystems team, to respond to the questions raised by this provocation. To follow-up, we are planning a research roundtable on 21 February 2023 with key researchers and experts where we will probe and challenge this three-part series of provocations, related to international data ecosystems, physical infrastructure and dynamics of power. If it is of any interest, please get in touch. Resources: To view connected research, see our collaborative bibliography – a curated, living repository of books, reports, podcasts and research papers compiling some of the brilliant work of researchers from around the world interested in how data and digital technologies shape new geopolitical dynamics worldwide. Please check out the ODI’s Data as Culture website if you want to know more about the programme.