What is a digital twin?

A digital twin is a digital representation of physical asset, which can be used to monitor, visualise, predict and make decisions about the physical. This can encompass a wide variety of different things – for example, Formula One teams use digital twins of engines to evaluate and make decisions about performance. Or, Northumbrian Water created a digital twin of Newcastle’s water infrastructure to enable it to improve its network and understand how best to respond to potential events like flooding or drought.

The Open Data Institute (ODI) ran its digital twins research project between spring 2019 and March 2020.

Why digital twins?

The ODI started its research into digital twins following the Centre for Digital Built Britain (CDBB)’s launch of its National Digital Twin programme in the UK – a long-term programme that aims to advance the creation of digital twins in the UK, and beyond. The ODI is also a member of the Digital Framework Task Group – a body set up by CDBB to lead the development of a framework for creating digital twins.

The ODI began its own digital twins project to help guide the CDBB’s programme. But beyond guiding CDBB, the digital twins project is one that sits close to the ODI’s vision. A key pillar of the ODI’s manifesto is robust data infrastructure; and, as stated on the project page, this project served as ‘a significant opportunity to strengthen the data infrastructure associated with our national built environment in the UK. It represents one of the country’s most significant areas of government and private investment.’

The digital twins project was funded by Innovate UK as part of the ODI’s R&D programme.

The digital twins project at a glance

- The ODI’s digital twins project ran from 2019–2020, following the launch of the Centre for Digital Built Britain’s National Digital Twin programme (which the ODI had already had some engagement with)

- The team conducted interviews with eight experts working in relevant areas, created a prototype of a digital twin for a building management system model, and held internal workshops on the future of digital twins

- The ODI published an annotated slide deck containing the project’s findings

- The team created a variety of outputs, including articles, weeknotes, a guest post and a podcast, which were shared with over 11,300 subscribers via The Week in Data and with over 50,000 followers on Twitter

- The project page gained over 1,300 page views between May 2019 and November 2020

Not sure what a digital twin is? You're not alone. We've been exploring people’s understanding of ‘digital twins’, and gathering views about how a national digital twin might be implemented: https://t.co/kkdKs4io8I #ODISummit https://t.co/leqQwFOqz2 — Open Data Institute (@ODIHQ) November 12, 2019

Project overview

The Digital Framework Task Group, which the ODI is a member of, has the goal of developing a national digital twin by 2050. By ‘national digital twin’, the ODI means a connected network of digital twins which feed into one another on a national scale, rather than one all-encompassing digital twin of the nation.

To best guide this goal, the ODI team’s research into digital twins mainly focused on four areas:

- Uncovering how digital twins work

- Researching whether the idea of networking digital twins all the way to a national scale was reasonable

- Exploring whether we could inform the development of a network of digital twins in a sustainable, open and trustworthy direction

- Researching how data can be shared between digital twins in a secure and resilient way

In terms of approach during the discovery phase of the project, the team used a combination of user research, prototyping and workshops.

For user research, the team interviewed eight experts working in relevant areas. This included four researchers working on areas related to simulation modelling, two representatives from the private sector, and two members of the Digital Framework Task Group. From this, the team gathered key insights into how experts currently understand digital twins, the pain points that people come across while creating and implementing a digital twin, and current opinions on the development of a national digital twin. These insights were instrumental in the next phase of the project, in which the team developed guidance and recommendations by addressing the questions and concerns that were raised in the interviews.

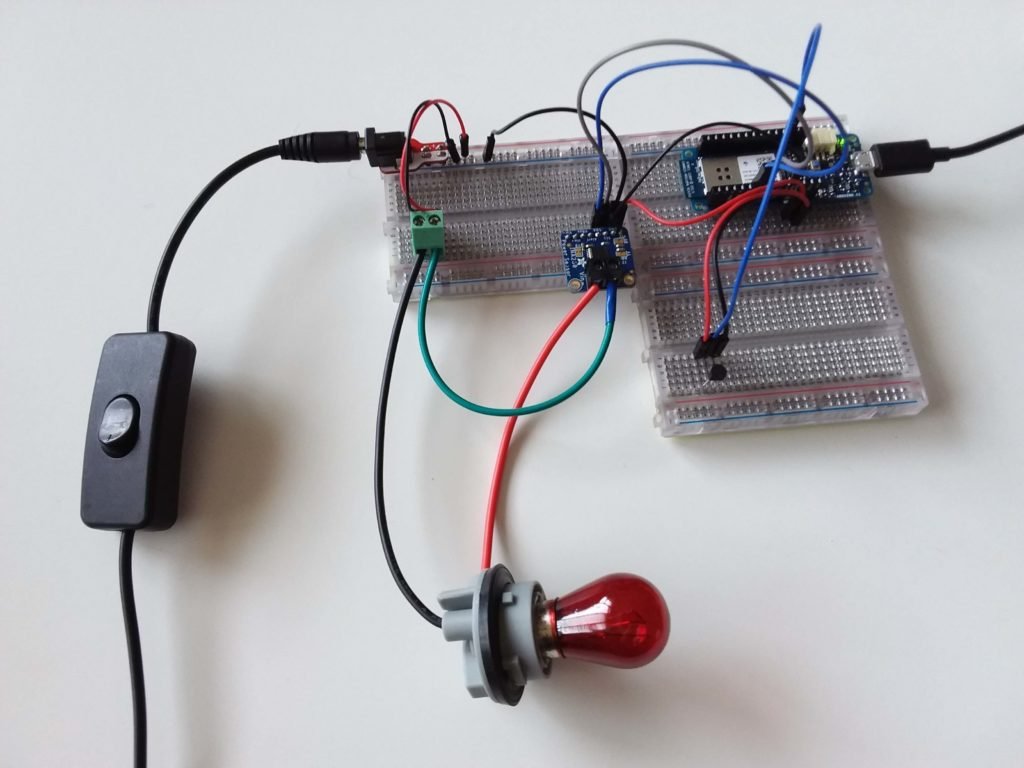

For prototyping, the team used a mix of hardware and open source software to build a model of a building management system and a prototype of its digital twin. While user research is nothing new to the ODI, prototyping was a somewhat novel approach. Usually, the discovery phase of the ODI’s R&D projects centres around desk research or user interviews. However, the technical nature of digital twins coupled with the team’s expertise (several members of the team had technical backgrounds) presented an opportunity to explore the benefits and drawbacks of prototyping as a research tool.

In the workshops, the primary focus was looking to the future of digital twins, rather than understanding the current landscape. From research, the team understood that the future of digital twins could take several different forms, and a variety of digital twins networks could emerge and scale. To better understand what shape the future of a network of digital twins could take, the team held futures workshops internally which examined how digital twins – and in particular, networks of digital twins – might develop.

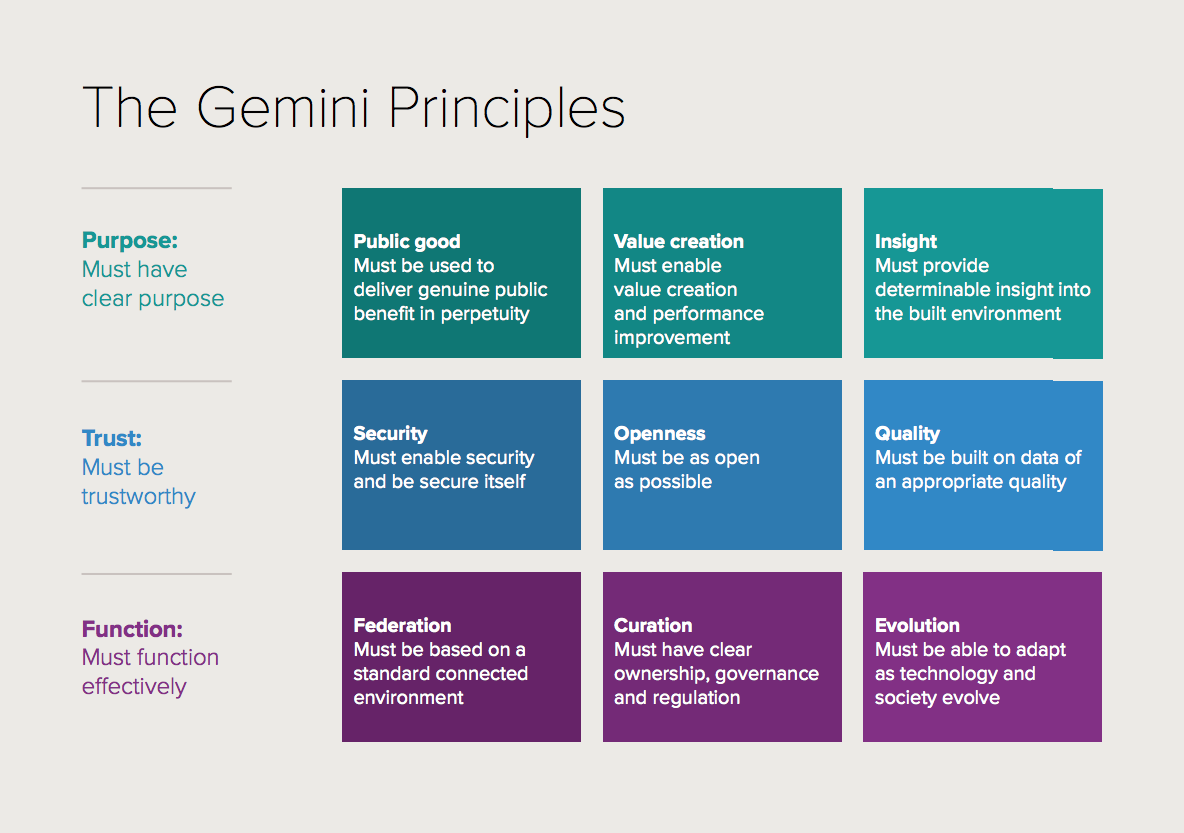

The aim of these workshops was not to accurately predict the future of digital twins, but to identify forces that are likely to impact the development of a national digital twin and core principles to follow. From this, it was decided the national digital twin would have to be:

- Federated – it would have to be several interconnected digital twins, not just one all-encompassing twin.

- Never complete – new infrastructure is constantly being introduced and developed, so the network would have to develop to match.

- Cross-sector – creating cross-sector networks would allow us to ask questions that go beyond one digital twin or even one sector.

- For everyone – the national digital twin would likely inform policy, and would therefore affect everyone.

This approach follows the Gemini Principles, set out by the CDBB – with input from the ODI – which outline that the national digital twin must: have clear purpose; be trustworthy and function effectively.

As laid out, the digital twins project took multiple approaches and tackled various areas of concern. This meant that communicating the research was an important consideration.

Like the methodology for research, the team tried several different approaches to do this. For example, for most (but not all) ODI research projects, the main output is a report that presents practical findings. However, for the digital twins project, these recommendations were delivered in the form of an annotated slide deck.

And, to document the process along the way, the team created an in-depth article reflecting on historical learnings that could guide the development of the national digital twin, a series of weeknotes documenting the process of building a digital twin prototype, and even a podcast with the chair of the Digital Framework Task Group.

What went well

Firstly and perhaps most importantly, the project allowed the team to provide CDBB and the Digital Framework Task Group with valuable insights about the concepts of a digital twin and a national digital twin. These insights ranged from a complex understanding of the current digital twins landscape, to identifying principles that will need to be in place for a national digital twin to work. For example, the ODI’s Head of Research and Development Olivier Thereaux gave a webinar for the CDBB’s Digital Twin Hub, in which he outlined the ODI’s learnings from the project. This included three key reflections on the development of a network of digital twins:

- The concepts of digital twins and a network of digital twins are scalable. A large-scale network of digital twins is not only possible, but will create value far beyond the value of the individual digital twins.

- Creating a large-scale network will not be an easy task – it will require a lot of time and effort. It will likely take decades to develop and implement.

- For it to be an open, trustworthy network that works for everyone, it will require both a bottom-up and top-down approach. There’ll need to be rich use cases that can encourage others to buy-in to a network of digital twins, but we’ll also need a set of principles and a shared language.

Another success within the digital twins project was the approach to research. There was originally concern that prototyping might just serve as a longer path to insights that could have been gathered through desk or user research. However, this was not the case. The process of actually developing a digital twin meant that the team had to be completely comfortable with the ins and outs of the concepts involved – there is no room for misunderstanding when you are doing the ‘doing’. As Senior Developer Rachel Wilson, who developed the prototype, put in one of the weeknotes documenting the process, if she had stuck to just writing about how she ‘imagined the system would turn out’, she ‘would have remained wrong’ in her assumptions about digital twins. For example, through the process of prototyping, the team learned that a digital twin doesn’t need to be built from scratch, that not everything about a digital twin has to change with scale, and visualisation doesn’t have to be ‘realistic’ to be useful.

The method in which the team communicated their research was also a key success within the project. Prior to creating any content, the team conducted a rigorous analysis of various audiences, their needs, and the types of outputs that would work for them. This process informed the outputs used within the project, which has resulted in better content that resonates with the audience.

For example, the annotated slide deck that was created in place of a report can be shared with organisations as a knowledge product in and of itself, contains links and citations should people want to learn more, and serves as a quick and accessible way for people to get up to speed with the project. Anecdotal testimony suggests this has worked well (so far, no one has requested a report for the digital twins project instead of the slide deck), and viewership is in line with what we’d expect. While it’s hard to ascertain concrete viewership figures for the slide deck itself, this digital twins project page (which hosts the slide deck) received just under 500 page views over the first six months of its publication, compared to a similar project report page’s 664 views in its first six months.

Further, the documentation of processes, like the weeknotes on prototyping, brought a new level of transparency and openness to the project, and means that lessons learned about processes can be learned and shared both internally and externally.

Nicely relevant article for my work world: A match made in heaven: how ‘digital twins’ can help bring a better built environment. https://t.co/Kw1ZyiBqgT via @ODIHQ — David Smith (@SmithDavidM) February 8, 2019

What was challenging

Of course, no project is without its challenges.

Much like many projects that have taken place in 2020, perhaps the biggest challenge the digital twins project faced was the effects of the global pandemic and the subsequent lockdown. The team had aimed to publicise and create buy-in for the outputs of the project through a series of events throughout February and March 2020. However, the UK’s nationwide lockdown – and the pandemic in general – meant that this was not possible. This was a real challenge as those final months of the project were due to play a vital role in ensuring the research got in front of the intended audience. The timing meant the team had to quickly pivot away from these plans.

Next, the project covered areas of research that were so broad, it could be hard to ground the research into useful and actionable insights. The Digital Framework Task Group is looking all the way to 2050 with its work around a national digital twin, and there currently aren’t many use cases of networks of digital twins to work from. As such, it was easy for research to shift to being too general, or snowballing into something that was less useful. Certain processes did help ground the work – like prototyping and developing use cases – but this still could have been done more. For example, in the futures workshop, it was hard for the participants to accurately discuss potential futures without much of a developed landscape to springboard off, and conversation often slipped into generalities.

The broadness of the topic also meant it could be hard to communicate the research, especially while trying to avoid buzzwords or jargon. As mentioned, the team conducted an output mapping exercise in which they considered the potential audiences for the projects, their needs, and the content that would best resonate with them. However, this was a difficult (and long) process. It could be difficult to know what information would be most helpful to share and to who, and how best to convey that information. This challenge was also amplified by the technical nature of digital twins – it could be difficult to know to what level of technical detail to go into, and how to make this information accessible (especially when part of this project involved the hands-on work of developing a prototype).

Finally, it could be hard to predict and measure the impact of the experimental approaches the team took. As we’ve covered, both the approach to research and the approach to communications were somewhat different to those taken in previous projects. As with any new approach, it was hard for the team to know what would work, and what wouldn’t. As such, the team risked spending time on endeavours that wouldn’t pay off, or could be done more easily through other means. Further, the impact of this experimentation is hard to measure. For example, while there’s anecdotal testimony from the audience that delivering the final output in the form of an annotated slide deck worked well, and we can point to page views as an indicator of success, it’s hard to quantitatively prove that it resonated with the audience better than a report would have without having concrete viewership figures for the slide deck itself.

What have we learned for other research projects?

The digital twins project produced some key lessons for the team to take forward:

1. Desk research and user research do produce meaningful insights, but they aren’t the only approaches. Other approaches – like prototyping – can uncover findings that you otherwise might have missed.

2. Similarly, reports aren’t the only way to indicate outcomes. Reports can be a good way to communicate the findings of a project. However, they’re not the only method – other outputs can do the same job, and may resonate with an audience better.

3. Leading on from this, actively mapping outputs to audiences can be difficult, but is a worthwhile exercise. This process proved extremely helpful not only for the main output of the project (the annotated slide deck), but for various pieces of content created throughout, including the weeknotes and the podcast.

4. Workshops focusing on the future can be difficult. There aren’t many concrete use cases of networks of digital twins, and without use cases, it can be hard to workshop possible futures. As such, for future ‘futures workshops’, the team agreed it would be more beneficial to have experts in the room to help identify what would be technically and institutionally feasible in the future, and to also have more fleshed-out use cases to explore.