There are over 1.1 million households in England on the social housing waiting list, even though there is enough brownfield land to build an estimated 1 million homes.

In 2020, engineering and design consultancy company Atkins undertook a discovery project, funded by Lloyds Register Foundation and supported by the Open Data Institute, to identify how well currently open datasets can support developing insights into contamination of brownfield sites, and comparing that approach with existing commercial and unused datasets.

Back in March 2020, the Lloyd’s Register Foundation and the ODI offered a stimulus fund to help projects to increase access to data and drive innovation in the engineering sector – with an emphasis on improving safety, and this is one of them.

Key facts and figures

- Critical sources of contamination are currently only found in non-open datasets.

- Datasets already exist that could be made more open to help improve decision making and reduce costs associated with developing brownfield sites, particularly for smaller developers, and help address the national housing crisis.

- There is unused data held by companies like Atkins and their customers which, if shared in ways that built trust, could unlock further value.

- There is an opportunity for industry to collaborate and unlock the power of location data about brownfield land contaminants. These conversations will be important to support Government housing commitments and deliver the ambitions in the UK Geospatial Data Strategy.

View Atkin's latest report: Improving safety in brownfield development

What was the challenge?

Currently there are over 1.1 million households in England on the social housing waiting list, even though in England there is enough brownfield land to build an estimated 1 million homes. One of the biggest blockers in developing these sites are unknown ground conditions, especially where there is the potential for contaminated land to pose a health risk.

Ground conditions within brownfield land are known to have an impact on health and safety. For example, developing on or near a historic landfill can put workers developing the site at risk (e.g. encountering hazardous materials, such as asbestos) as well as causing health issues in residents (e.g. from the gas generated from breakdown of waste materials).

This discovery research project led by Atkins aimed to identify how well currently open datasets can support developing insights into contamination of brownfield sites, and comparing that approach with existing commercial and unused datasets.

Even though we know that the ground conditions on brownfield sites can have a big impact on health and safety, the levels of contamination within the ground are not yet being recorded or made available in the same systematic way. For example, often these datasets are under commercial terms, which may make it harder for some to access.

The creation of data for specific projects or surveys being used once and never again is a challenge faced across many working on the built environment

Repeated surveys of the same ground by different developers are a typical example of this problem. A combination of data being held on a project by project basis, a lack of visibility of data acquired and difficulty gaining access for reuse mean that developers spend time and money repeating data collection activities.

The creation of data for specific projects or surveys being used once and never again is a challenge faced across many working on the built environment. The number of initiatives in place looking at different models for sharing data indicate the scale of the challenge and the potential value to gain.

How are Atkins solving the problem?

Building on previous and existing initiatives (such as Project Iceberg and National Underground Assets Register), Atkins framed their discovery project around three challenges to make data about underground infrastructure accessible.

- Creating an inventory of data that could determine whether brownfield land would be classed as contaminated.

- Identifying use cases to demonstrate how open, shared and closed data about brownfield sites could reduce unknown risks on site.

- Creating a framework to encourage increased sharing of data about brownfield sites and contaminated land.

To ensure they had a common view of data sources, the team used ODI guidance to create a data inventory. They drew on the numerous projects Atkins are involved in each year that require access to data about brownfield sites or understanding levels of land contamination. The team interrogated their internal database to identify data from relevant past projects. The search included 1500 projects from the public and private sector and highlighted the range of organisations holding data on this subject.

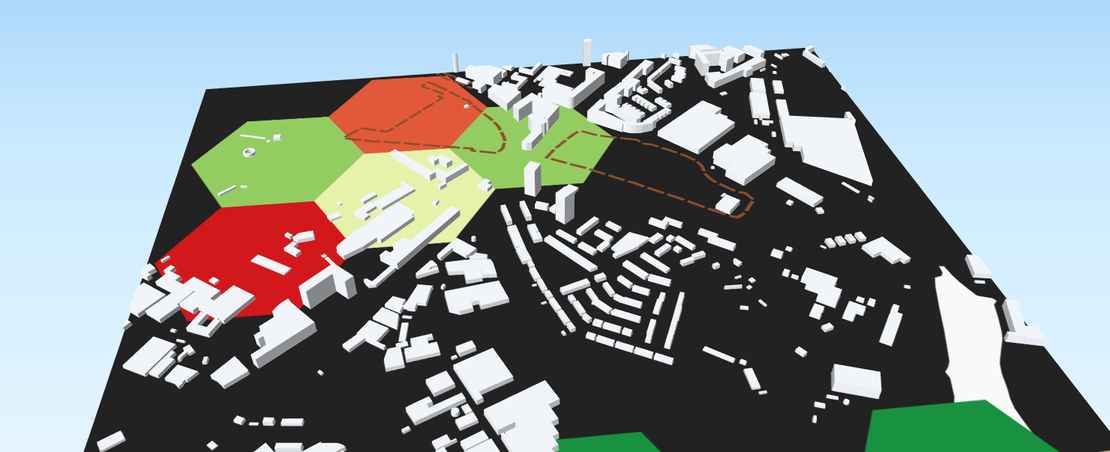

Focusing on two use cases, the team examined the data available to understand contaminants in land, and identify gaps at site specific and national levels.

- At site specific level, using the example of a gasworks site, the team were able to understand the impact of using only open data or a combination of open and proprietary data to understand the risk of contaminants on site.

- To understand risk at a national level the team used data on ground investigations and environmental monitoring held in their OpenGround system (a cloud-based platform). This data is only available on a project by project basis so the team extracted the relevant layers, prepared the data into a standardised format, and aggregated it into a national dataset for their use.

To understand risk at a national level the team took a novel approach of looking at individual survey data and exploring how it could be aggregated to help provide more insights into land contamination.

In forming a common view of data sources, the team created the first open access land contamination data inventory

In forming a common view of data sources, the team created the first open access land contamination data inventory and published Atkins’ first public Github repository. They chose to publish these outputs openly to encourage collaboration across the community to maintain and improve the data inventory. The Github repository hosts both the inventory and the code developed to access multi-project data via OpenGround Web API to enable scale analysis of existing data.

What was the impact of taking this approach?

Government policy commits to both supporting smaller developers financially to encourage innovation in the kind of homes that are built and the way they are delivered and to:

“work with local leaders to regenerate local brownfield land and deliver the homes their communities need on land which is already developed.

We know the ground conditions on brownfield sites can have a big impact on health and safety, site development costs and design constraints, yet these data are often only available under commercial terms at cost, which can make it harder for smaller developers, who often have fewer resources, to access them.

The findings of both the national and site specific use cases investigated by Atkins, demonstrate that using only currently open sources of data leaves a gap in understanding health and safety risks. For example, site specific data omitted to identify the site had previously been used as a gasworks, and therefore posed an increased risk to safety and added costs for the developer.

The findings of both the national and site specific use cases investigated by Atkins, demonstrate that using only currently open sources of data leaves a gap in understanding health and safety risks

Making more of this data openly available could drive down costs, by reducing the need for multiple surveys of the same ground and through earlier identification of site constraints (contamination risks and potential remediation required), thus reducing development costs and helping to deliver government housing commitments.

This project highlights the opportunity for industry to collaborate to unlock the power of location data about brownfield land contaminants. Due to the variation in the provision of information about reuse of data, Atkins have opened up conversations with clients about data reuse & licensing permissions. Initial discussions have begun with key-stakeholders in this sector including AGS, Geospatial Commission and Bentley and should support delivery of the ambitions in the UK Geospatial Data Strategy. If organisations within the sector are able to align on the way they will access, use and share data this could make things much more streamlined, improving efficiency and reducing costs on projects. The network effects of this could be widely felt.

This project highlights the opportunity for industry to collaborate to unlock the power of location data about brownfield land contaminants.

Existing survey data is not well standardised, because it is expected to have limited use. Through some even simple standardisation, it could be possible to reuse this information in new ways, including the creation of an aggregate dataset. This project has highlighted some of the initial areas of focus and areas for further work to maximise value from this data.

What lessons did they learn?

This discovery project threw up a number of challenges and learning points.

- There are a vast range of public and private sector organisations holding data on this subject, therefore accessing all the available data isn’t straightforward. It can often be quicker and easier to buy environmental data from a reseller (e.g. Landmark and Groundsure) rather than approach each steward individually, as they have already completed the work to collate / aggregate the relevant information. However, purchasing data in this way can be costly, and could limit opportunities for smaller developers.

- Consultancy firms often purchase the same data multiple times for use on different projects, this is due to a combination of a lack of visibility of data acquired internally, so projects aren’t aware of what is already available, and unclear information on reuse. Our manifesto outlines what is required to treat data as an asset to maximise its value to individual firms, as well as wider society.

- Local Authority Planning Portals contain rich historic information however often data formats are proprietary and it is difficult to extract and analyse the data. The team needed to use machine learning to pull out historic data and information from pdf’s.

- Data standardisation is very much project by project, there is no overarching industry strategy. Due to this, it was not initially possible to easily select and extract all relevant data, across the range of projects, in one go. To overcome this challenge the team tailored commands within an API to retrieve the data. Retrieval of data is a common challenge within consultancies; consultants routinely charge for time under project delivery, which often doesn’t account for data management time, therefore there is often no dedicated resource within organisations to tackle data management issues and they are picked up informally by hobbyists. Investing in a stronger data infrastructure, as set out in our manifesto, with agreed standards and guidance for the access, use and sharing of data, will ensure organisations and communities are able to access and maximise value from it.

- Data about contaminated land can be highly technical and difficult to understand for non specialists. Involving a domain specialist within the team was critical in terms of understanding practices in the field, and terminology used within the data. The team found they drew on this domain knowledge much more than originally anticipated. This also raised questions about how an aggregated dataset, or sharing of survey data more widely, might need to be done cautiously so that it is properly interpreted.

Key tips and advice

Create a data inventory

Focussing on the purpose of the inventory, for example to address a particular challenge or topic, will ensure it is as useful as possible and will contribute to a stronger data infrastructure. Involving domain experts will also help with identifying the key information to capture. For example, in this case staff experienced in completing Preliminary Risk Assessment (PRA) desk study reports input to the inventory scope.

Invest in data science skills and knowledge on projects

It took a lot of technical expertise to access, use and share data within this project, requiring specialist data skills and knowledge in conjunction with domain expertise. Tackling these types of challenges with a multi-discipline research team increases the skills and knowledge available to a project. Building data skills required for the future of the profession as a key activity outlined in our manifesto for sharing engineering data. There is a role for professional bodies, private sector companies, universities and research organisations to include these skills in their curriculum and professional development activities.

Communicate and collaborate early

Due to the range of organisations involved in stewarding data on land contamination, communication and collaboration across the industry to maximise utility of data is key. Include a range of stakeholders within the land contamination business relevant to your project (e.g the AGS Committee, laboratories, contractors, consultancies, regulatory bodies, the British Geological Survey, local planning authorities and industry bodies) to agree a unified data structure and robust standards. Including the sharing of data in contracts, so everyone is clear on their responsibilities as projects are agreed, could also be another way to maximise value from data across the geotechnical and geo-environmental industry and its stakeholders. The importance of stewarding data for collaboration is highlighted in our manifesto.

What’s next?

This project has been a catalyst for internal conversation at Atkins about the value of an open approach to access and reuse of data. Atkins are keen to continue the conversation on unlocking data about brownfield land. They plan to continue;

- Engagement with the Geospatial Commission, working with them to align this research with the four missions outlined in the Geospatial Strategy 2020-2025. These further goals will likely be aligned to the development of housing specifically.

- Working with the AGS to improve their data formatting and opening up their framework to make it more accessible to a wider audience.

- Opening up conversations with clients about how they can open up data on their sites and contribute towards an open data ‘future’.

- Further research into the other datapoints available in the AGS data currently stored in the OpenGround database.

- Promoting community contribution to the contaminated land data inventory. For example, by establishing an agreed ranking system to indicate the level of importance of datasets to the community.

Get involved

If you want to get in touch to speak to the team involved in the project or to discuss a project you’re running yourself which you need some support with, please get in touch